By: Erika López LaraLearning about climate change can be overwhelming. When I first began to unravel the intricacies of climate change, I couldn't help but wonder why all of us weren't urgently working on a solution. After some time, I realized that it is not that simple.

I am originally from Mexico, where according to CONEVAL, in 2020 43% of the population was living in poverty and 8% in extreme poverty. Unfortunately, these numbers are not an isolated case, worldwide, 10% of the population lives in extreme poverty. How can you care about climate change if you and your family do not have enough to eat or a place to live? You must set your priorities. When we consider the projections regarding world’s situation with the raise in the surface temperature, the long-term situation will be worst. As natural disasters such as hurricanes continue to increase, how will people with limited resources leave the cities to safety? How will they eat if they are living hand to mouth? Unfortunately, the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC states that developing countries are expected to suffer the most negative impacts of climate change due to their limited capacity to anticipate and respond to the climate crisis. Climate change will exacerbate the vulnerabilities of these countries and their population living in poverty affecting access to water, the health of people, food production, livable land, etc. However, it is not only low-income individuals who will be the most affected but also the minorities. For example, in the US, Black, Latino, Native Hawaiian and Asians communities are more likely to live in areas where the impacts of climate change are the most severe. This is reflected in high mortality rates due to extreme temperatures, labor hour losses in weather-exposed industries, floodings, etc. This makes climate change not only an environmental problem but a social and racial concern. Climate justiceis the term used to define climate change as an ethical, political, and social problem and emphasizes that solutions must be holistic. Moreover, it acknowledges that those most affected people are the least responsible for the climate crisis. It makes an urgent call for a genuinely sustainable future where society, economy and the environment are treated as equal. As an urgent response for this unethical global warming, in 2015, the United Nations proposed the sustainable development goals for 2030 which can be seen as an international step towards climate justice. Unfortunately, a preliminary assessment in 2023 indicates that only 12% of the 140 targets are on track and 30% are not or have even regressed below the 2015 baseline. This urges the governments, industries, and society to keep working on making them a reality. Another international effort is The Green Climate Fund, which is a fund to support developing countries in reducing their emissions and helping their population adapt to climate change. Between 2020-2023, developed countries contributed to this fund with more than 9 billion dollars which are expected to avoid the release of 2.4 billion tons of CO2 and help 666 millions of people to adapt . Fortunately, it is not only have the governments taking action on climate justice but also many grassroots organizations such as Indigenous Climate Action. This NGO focuses on defending the rights of indigenous peoples and preserving their knowledge to develop climate solutions. WE ACT is another example of the efforts being made. This organization works on informing and engaging people of color and/or low-income residents to participate in the creation of fair environmental health and protection policies. These examples demonstrate that there are people fighting for a fair world, a crucial element to get holistic solutions for climate change. However, we must remember that being able to join an activist organization and being informed is a privilege that not all the population has. Therefore, individuals who have the privilege of caring about climate change should act and amplify the voices of the underrepresented groups. It is urgent for everyone to engage in a global partnership because climate change knows no borders, and we are all in this together. COP28 promises to be inclusive and “for all” so let’s hope that during negotiations this inclusivity is prioritized and stronger commitments are made. References: http://www.coneval.org.mx/Informes/Pobreza/Rezago_Social/Rezago_Social_2010/Rez_soc_A GEB/Base de datos.zip http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_SummaryVolume.pdf https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-09/climate-vulnerability_september-2021_508.pdf https://centerclimatejustice.universityofcalifornia.edu/what-is-climate-justice/#social-racial-environmental-justice https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/what-climate-justice-and-what-can-we-do-achieve-it https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/ https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/20230501-gcf-1-progress-report.pdf

1 Comment

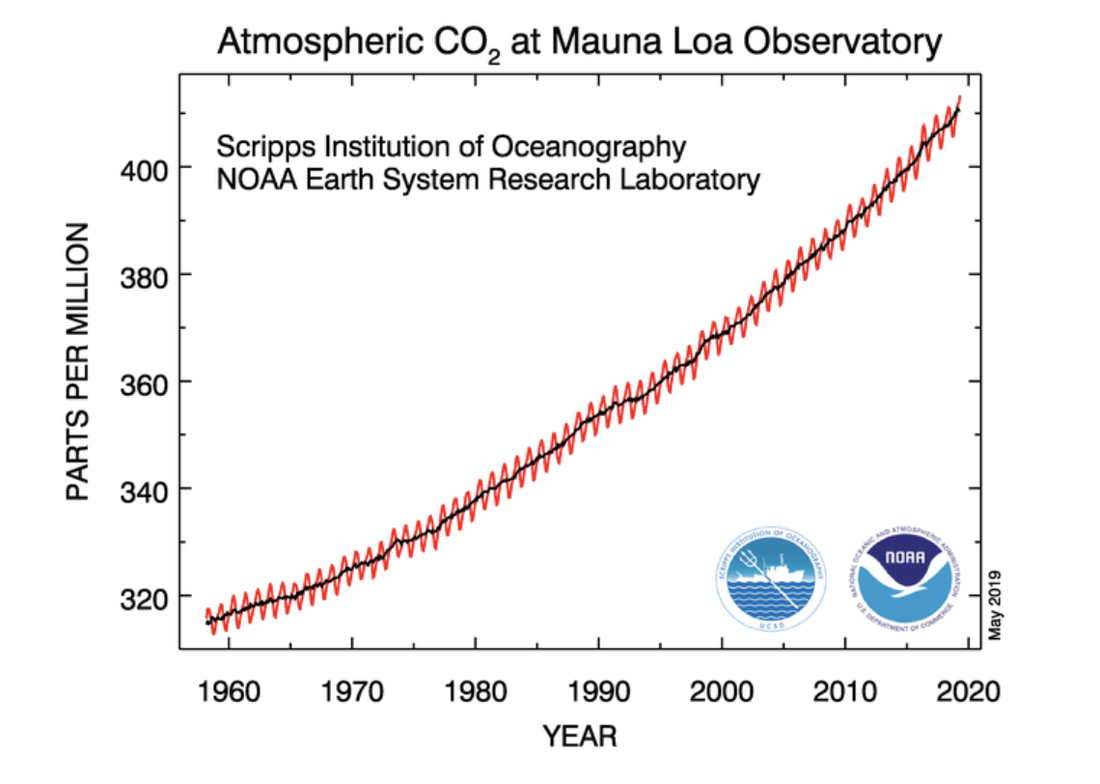

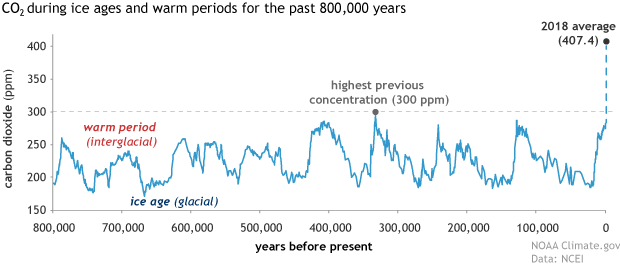

by: Aminda Cheney-Irgens For readers not well acquainted with the rising carbon concentration in our atmosphere, I include the Keeling Curve, developed by Charles David Keeling. Why is this figure important? As we look at the x axis, showing the progression of time from around 1960 to the present day of 2019, and the y axis, demonstrating the parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere, a clear trend emerges: atmospheric carbon concentration is increasing. This isn’t a singularly reported finding, nor is it a common trend observed in the geologic history of our earth. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA, and countless other agencies and researchers have asserted the same conclusion: the amount of carbon is higher than it has ever been before, and this is and will have drastic effects on our world and environments as we know them. Take a look at this next figure. We can see that throughout the ages, there has been a cycling of carbon, between green periods, when plant life takes carbon from the atmosphere, and ice ages, when carbon levels can increase. On the very far right, where the graph spikes up well above the dashed line, is where we are now. This represents the highest carbon concentration known to ever have occured on the planet! So what does public transportation have to do with atmospheric carbon?

Limiting carbon emissions is important for our communities and our environment. There are many health risks associated with poor air quality in highly populated areas, many of which are due to increased traffic.3 According to the US Department of Transportation, “transportation accounts for 29 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States,” which is over one fifth of our emissions.3 A study by the Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP), sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration, titled “Costs of Sprawl - 2000,” found that a main factor of energy usage growth in the U.S. is due to single occupant vehicles.3 Use of public transit can curb this spike in carbon emissions. Public transit heavy rail systems such as subways and metros produce 76% less of a carbon footprint per passenger than when people choose to drive in their own cars, light rails have 62% less emissions per passenger, and bus transit creates 33% less (Check out Public Transportation’s Role in Responding to Climate Change (PDF)).3 According to the DOT, “public transportation encourages energy conservation, as the average number of passengers on a transit vehicle (10 for bus, 25 for a rail car) far exceeds that of a private automobile (1.6).” 3 By sharing vehicles and investing in public transportation, we can address the carbon-heavy impact of single occupancy vehicles. The U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy states that “we already know that public transportation reduces pollution and eases congestion on the road,” an assertion supported by the United States Department of Transportation.3,4 This is also reflected in a 2004 study by ICF International which demonstrates that the use of public transit saved 947 million gallons of fuel that would otherwise have been used in private vehicles.3 As the DOE explains, “as communities become more sustainable, many transit fleets are switching over to cleaner, alternative fuels and technologies,” highlighting communities like Louisville, Kentucky that have switched to electric buses.4 By encouraging the use of public transit, we can promote compact development, which means that less land is set aside for construction of roads and more is available for uses like parks, agriculture, and community development efforts.3 Simply by having fewer roads, contaminated water runoff reaching our water supplies is also decreased. This is supported by a study titled “Costs of Urban Sprawl,” done by the Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP), sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration, stating that “compact development ... can improve water quality through reducing the amount of impermeable surface runoff and preserve biodiversity through reducing fragmentation of natural habitat.” This same study asserted that “compact development could save the United States nearly 2.5 million acres of land.” Another study by the TCRP, titled “Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospects,” found that encouraging city development around the public transit networks can “reduce pressures to convert farmland and environmentally sensitive areas into housing and commercial development.” Not surprisingly, having greenspace is a crucial aspect of removing atmospheric carbon, and preventing the use of this land for road construction is important for addressing carbon emissions. But is it really worth it? To those who might argue that public transportation is not sustainable because so few people use it, I have news for you: you can change this! Take the initiative to find routes that can take you to work, to the mall, to museums, or other locations you frequent. There are countless routes that have been planned to drop off at convenient locations. Instead of paying attention to the road, you can take advantage of that time to get something else done (maybe that article you haven’t read for your class yet, or the book you just checked out from the public library). If you feel that the public transit in your community is not convenient, get involved in your local government, write your city council, and encourage the redesign of these routes so that they can actually serve the community! Many cities have successfully redesigned routes to have more buses run on frequently traveled days, and have fewer vehicles running on days when ridership is low. The issue many public transit planners run into is ensuring that routes are still accessible to those who rely on public transit, and this is extremely important if our public transportation is going to achieve the goal of being equitable (Check out the article “The "Transit Isn’t Green Because It Runs Empty” Line” by Public Transit consultant Jarret Walker.) Baxter Krug Chemistry and Communication - Angelo State University

Jack GreenSenior, Louisiana State University  “We’re about protecting our water. We’re about protecting our sacred places. We’re about protecting our sovereignty,” said Dabe Archambault II, Chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe during interview with ABC news in 2016 on the Dakota Access Pipeline. In 2017, after months of protests by environmental activists and the Sioux Tribal nation, construction on the Dakota Access Pipeline was completed. The pipeline is widely considered by tribes as a violation of sovereignty and by environmental activists as a continuing threat to the drinking water of the region. The structure of U.S. tribal consultation policy was not strong enough to give the Sioux Nation substantial influence on permitting for a project that would affect their land. The pipeline decision has been a focusing event for many Democratic candidates running for president and other progressive policy makers in the U.S. who are calling for the integration of a land rights policy that is internationally considered a “best practice.” Free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) is a standard of indigenous land rights policy that requires just what it implies, informed consent by indigenous peoples for development projects or government policies that could impact their territories or peoples. FPIC is the difference between simply a requirement to consult with indigenous peoples over outside actions that can affect them and giving those communities a final say on whether those actions can be taken out at all, essentially giving the communities a “veto” power in the strictest interpretation. In terms U.S. proposals, a number of 2020 Democratic primary hopefuls have released their own with various degrees of specificity. Read below for excerpts of these proposals and click here for a longer essay on the history of FPIC and environmental self-determination for indigenous peoples. Senator Elizabeth Warren Senator Warren’s proposal is by far the most lengthy and detailed platform for indigenous issues. Warren calls for the revocation of Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipeline permits on the basis that they did not receive the consent of the indigenous communities that they affect. The proposal also states “respect for tribal sovereignty means that no project, development, or federal decision that will have a significant impact on a tribal community… should proceed without the free, prior, and informed consent of Tribal Nations concerned. Secretary Julian Castro Secretary Castro’s proposal addresses a need to “modify and codify tribal consultation requirements,” ensuring tribes have judicial recourse if their input is not considered during consultation. He goes on to call for the end of “leasing of lands for fossil fuel exploration and extraction,” and requiring “free, prior, and informed consent” of tribal communities on infrastructure projects that affect them. Senator Bernie Sanders Senator Sanders’ tribal policy platform has a bullet point calling for a Green New Deal to undo damage inflicted on indigenous peoples and to “stand with Native Americans in the struggle to protect their treaty and sovereign rights.” H.Res.109 By Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez In addition to these campaign proposals, it is worth mentioning that U.S. Representative Ocasio-Cortez’s 2019 H.Res.109 Green New Deal Resolution calls for “obtaining the free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous peoples for all decisions that affect indigenous peoples and their traditional territories… and protecting and enforcing the sovereignty and land rights of indigenous peoples” as a standard to achieve the stated goals of the proposed Green New Deal mobilization. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed