|

Back in December, Friday of the second week of the COP 21, Jill, Greg, Prakriti and I spent the day waiting for the announcement that an agreement had been reached. Everyone was going to adopt the Paris

The indigenous people that aren't a part of a country. The definition of an indigenous person is someone who has a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory, and their cultural or historical distinctiveness from other populations that are often politically dominant. (1) Now under this definition people such as Native Americans on a reservation are included, and while they are definitely affected by climate change (everyone is), those who live in a non-developed region are not taken care of at all. If you're wondering if they were mentioned at all in the Paris agreement click here to learn more. Many indigenous people are taking a stand and spreading the awareness of exactly how large the impact of climate change is to their people. A few of us were lucky enough to meet Kisilu, a farmer from Kenya. He has documented the effects of climate change with a video camera and you can watch his documentary "Climate Change Diaries" and read more here. Sources:

0 Comments

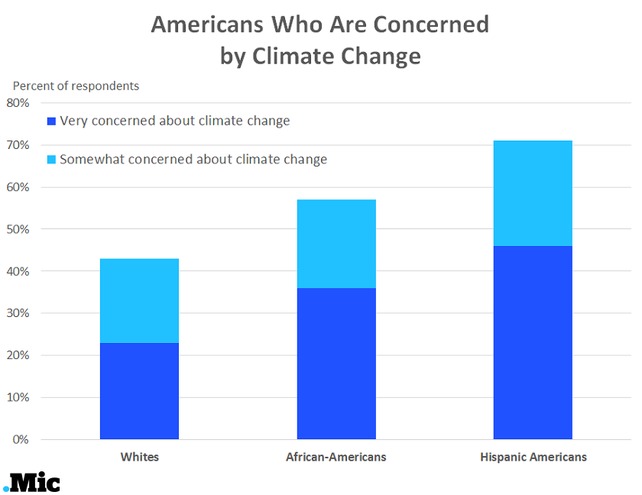

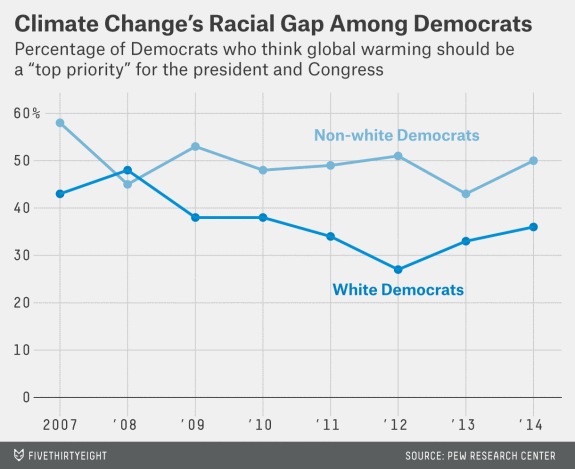

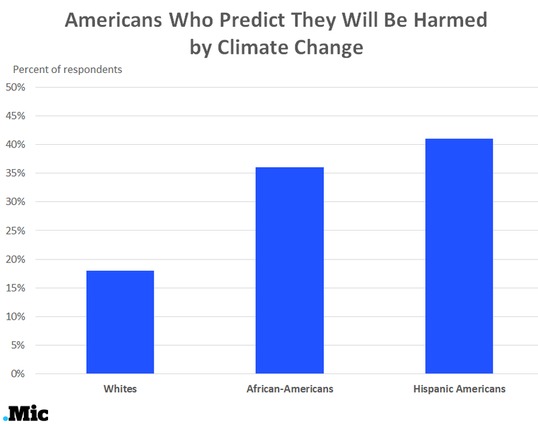

Indigenous peoples are some of the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, yet have contributed the least to the anthropogenic causes of climate change. On top of this, around 65% of the Earth's land surface is owned by approximately 370 million Indigenous Peoples from 70 different countries. Yet, Indigenous People are continually left out of international agreements and sadly the Paris Agreement is no exception. Now, if you read the entirety of the Paris Agreement (link at the bottom of this post), you will notice that there is one mention of indigenous people. That line states "acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES, local communities. . ." However, it is important to take note that this statement is in the preamble to the Paris Agreement, and the preamble is non binding. So even as countries ratify the agreement, there is nothing obligating them to follow what is written in the preamble. In addition, the statement starts with "Parties SHOULD." Any statements that follow the verb "should" are not legally binding, only when statements follow the verb "shall" are they legally binding. In early drafts of the Paris Agreement there was a section, Article 2.2, that focused on the protection of Indigenous Rights. However, strong opposition from the United States, European Union and Norway, resulted in the removal of this section and Indigenous Rights were diminished to that one small, non-binding statement in the preamble. There is one other reference to Indigenous Peoples' Traditional Knowledge in Article 7. The statement reads "Parties acknowledge that adaptation action should follow a country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory and fully transparent approach, taking into consideration vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems, and should be based on and guided by the best available science and, as appropriate, traditional knowledge, knowledge of indigenous peoples and local knowledge systems, with a view to integrating adaptation in to relevant socioeconomic and environmental policies and actions, where appropriate." While this statement doesn't make use of the non legally binding word "should" it does use the phrase "where appropriate" and in turn does not hold countries accountable for actually incorporating traditional knowledge into adaptation actions. Many Indigenous Rights leaders are also quick to point out that while there was a large presence of Indigenous Peoples at COP 21, most of their presentations were relegated to the Green Zone. The Green Zone was the zone open to the public and comprised of civil societies. There was much less Indigenous presence in the Blue Zone, the area where countries had pavilions and where the negotiations were actually occurring. Very few Indigenous leaders were even permitted to take part in the negotiations. However, Indigenous Peoples are not going to give up. They have already written letters, made speeches and held protests, showing their disappointment in the Paris Agreement, and plan to continue the fight on an international level to have their voices heard. Paris Agreement- https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf Other sources and references: http://www.iipfcc.org https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/annexed-rights-indigenous-peoples-un-climate-change-conference-2015 http://www.carnegiecouncil.org/en_US/publications/ethics_online/0113 Climate Gap: Less than 50% of White Americans are concerned by climate change. In contrast, more than 50% of African American and more than 70% of Hispanic American populations are concerned about the impact of climate change. "Like other pockets of environmental and conservation movements, climate change still suffers from the perception, and arguably the reality, that it is a movement led by and designed for the interests of the white, upper-middle class. Many people erroneously believe that interest in environmental issues is dependent on race, education, and class. To the contrary, growing numbers of people of color working in the environmental field and public polling demonstrate that reality often differs from conventional assumptions" - Angela Park Many climate briefings across the United States consistently feature predominantly male and all-white casts. As a result, people tend to view the movement against climate change as a movement created by and for white, upper middle class. The reality of the relationship between race and climate change in America is very different. Looking at some data, we see a massive gap in who cares about climate change. The face of people concerned about the effects of climate change on them, and the general public, is very different from the face of people that are highlighted by international media outlets. You may be surprised by this graph. Why would White Americans possibly care less about climate change than African American and Hispanic Americans? One plausible explanation is that a larger proportion of White Americans are republicans in comparison to African American and Hispanic Americans. Since republicans are less likely to believe in climate change than democrats, this matter of race could simply be attributed to political association. Is race a non-factor? The following figure shows shows that even within democrats, a larger percentage of non-whites believe that climate change should be addressed as a "top-priority" issue. Now that we've established that the race disparity in climate change isn't solely due to differences in political affiliation, lets get into some other factors that affect the relationship between race and climate change. The first factor, and a rather obvious one is vulnerability to climate change. The figure below shows that a much larger population of African Americans and Hispanic Americans believe they will be harmed by climate change. Are these groups justified in being more wary about climate change?

Hispanic Americans may be more attuned to the issue of climate change because a majority of them live in states that are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. For example, Florida is already experiencing more intense hurricanes and is exposed to the immediate effects of sea level rise. Similarly, California is experiencing drought and wildfires that are linked to climate change. Many African-Americans are concerned about exposure to pollution from the use of fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants. This pollution has led to the aggravation of the high rate of asthma in black communities, which is an important health risk that needs to be addressed in conjunction with regulations that will help intensify further anthropogenic climate change. African Americans and Hispanic Americans are more likely to recognize the danger of climate change and lead their communities in mitigation and adaptation. However, as socioeconomic status and race are linked, the communities most affected by climate change often have the least power in adapting to it. The support of all races and ethnicities will be extremely important as policies on climate change are created and implemented at present and in the future. This is not an issue that a single community can deal with alone. References: http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/the-racial-gap-on-global-warming/ http://environment.yale.edu/climate-communication/files/Race_Ethnicity_and_Climate_Change_2.pdf http://mic.com/articles/105120/new-poll-finds-something-surprising-about-race-and-climate-change#.ysRHMZQBh http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/05/08/climate-debate-isnt-so-heated-in-the-us/minorities-understand-the-threat-of-climate-change “There is no room for tokenism in climate change decisions.” My first day at COP21, I heard Dr. Spencer Thomas, Ambassador and Special Envoy for Multilateral Environmental Agreements in Grenada, say these words in front of an intent audience at the U.S. Center pavilion. Dr. Thomas was part of a panel discussion titled “Natural Solutions for Coastal Resilience” and the topic of race was definitely not a main theme surrounding the conversation, but the message of that one sentence is one that stuck with me throughout the week and still lurks in the back of my mind today.

Needless to say, Grenada is feeling the effects of climate change much more severely than we are here in the United States. But who is responsible? The world’s top carbon emitters are China, The United States, and The European Union. Grenada registers at a contribution of approximately 0% of global greenhouse gas emissions and emits 2.49 metric tons of CO2 per capita (15% of what the U.S. emits per capita). Grenada’s population is 95% black. The U.S. is 12% black. China and the European Union have a similarly minimal black demographic. More simply put: a black country suffers for white countries’ crimes.

On my final day at COP21, I was surprised when I saw the beginnings of a Black Lives Matter protest. Though I knew the relevance of this issue in the United States, I was not expecting to hear chants of “We can’t breathe!” and “Black lives matter!” while all the way in Paris. But upon further examination, their voices couldn’t apply to the situation more.

This brings me back to the original point by Dr. Thomas regarding tokenism. Not only must we continue to search for climate solutions, but we must begin to include the communities most affected in these discussions. Yes, every party was represented at COP21, but the input from the countries in the most trouble was often written off as “unreasonable.” The Paris Agreement was a step in the right direction, but to make the progress needed to save countries like Grenada, Vanuatu, and Ethiopia, they must be made a bigger part of the discussion. Sources: The World Bank, Personal Conversations from COP21 in December 2015.

The intense media exposure at this year’s COP talks in Paris has left climate change the hot topic of 2016. A big question lingering in my mind after the event was: what will be the financial outcome from environmental impact and industrial change in the next decade? In industry, some might complain that putting the planet’s wellbeing ahead of the dollar will ruin the world’s economy. However, I believe that the dollar has already done just that. Don’t get me wrong, I like money, as a concept - the world of trade without money would be complicated to master especially in this day and age. The issue is in how we quantify the value of the dollar. Dollar values can change based on a million different reasons, that’s what doesn’t seem logical to me, especially when you consider that the environment gets a raw deal.

Hear me out… What if the economy was more like chemistry? For example, you could compare chemical reactions to closed environment transactions. Meaning, you can’t create more value out of something that doesn’t merit it based on its intrinsic qualities. In a reaction, chemicals change from beginning to end but you always end up with the same amount of basic materials. In economy, this means you couldn’t trick the system to make something more valuable without paying for it somewhere else. Let's say the world system collapses, zombies run amuck - or whatever you imagine might happen in the apocalypse, at the fall of society. Initially, those dollars you have hidden in a jar in the back of your sock drawer or in a shoebox on the top shelf of your closet would be useful because people would cling to the idea that money can be used for obtaining goods. When it gets to the point when you don’t know where your next gallon of water or bite of food will come from, you probably won't care about money; you’ll want concrete goods. Now, this becomes more of a tangible economy comprised of basic exchanges. Back to chemistry - if you recall high school science class, you had to balance the chemical equations so that everything on the left matches everything on the right. The law of conservation of energy states that energy can’t be lost or destroyed but it can be transformed. Chemistry is a system where overall value is a constant. This is something fundamental to the core of everything that keeps balance in our physical world. When you apply this chemistry idea to money, value is no longer arbitrary, balance between materials and money becomes a must. The transformation in a chemical reaction as a result is the impact the economy has on the environment. Imagine a world where the dollar value of goods is based on what materials are actually made of, the energy it took to become what it is and the energy used for transportation and this would all be standardized. The idea that something is cheaper in one country over another would be based on the location of raw materials, not based on where you can get the cheapest labor to prepare or manufacture these materials. My concept would push for localized growth and economy. A system like this wouldn’t pull away from the idea that you get more for your effort, rather, it would raise the bar so people wouldn’t be able to take advantage of underdeveloped nations or people who don’t understand global economy. Thus, if a process requires a lot of material, it would be more expensive. If it requires more energy to make or transport, it would be more expensive. Financial gains would still be possible but without the use of cheap labor or environmental sacrifice, industrial ingenuity would be critical. In the end, the power to do something does not suggest you are doing it well nor does it give you the right to do it. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed