|

I was thrilled last week by the UNFCCC publishing an overview schedule of the two-week conference. As a young person attending an international conference for the first time, I have a limited idea of what to expect the week I observe conference proceedings. Scrolling the schedule, each day is assigned a vague but exciting theme: “EarthInfo Day,” “Farmers’ Day,” “Young and Future Generations Day,” “BINGO Day” (Business and Industry Day), “Education Day,” “Gender Day,” “Africa Day,” and “Climate Justice Day.” Then sprinkled throughout the two weeks are numerous events, side events, plenary meetings, workshops, dialogues, lunch breaks, showcases, sharings of views, and technical briefings. While the schedule seems rather daunting as I am not entirely sure what to expect on a day-to-day basis at COP 22, it’s important to break things down and understand the key issues that will come up. Climatenexus, a “strategic communications group dedicated to highlighting the wide-ranging impacts of climate change and clean energy solutions in the United States,” identifies seven key issues.

While a general grasp of these issues is only the beginning, I invite you to read more into these as our group of student representatives does the same in preparation for attending and making the most of our time at COP 22 in Marrakech this November! Sources: Marrakech Climate Change Conference Overview Schedule: http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/marrakech_nov_2016/application/pdf/overview_schedule_marrakech.pdf UNFCCC Provisional agenda and annotations for COP 22: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2016/cop22/eng/01.pdf Climatenexus summary of key issues: http://climatenexus.org/about-us/road-through-paris/negotiation-issues

8 Comments

The Presidential Election is set for November 8th, 2016 between democrat Hilary Clinton and republican Donald Trump. Voters are encouraged to understand the candidates' climate change views before casting a vote. Democrat Hilary Clinton

Hilary Clinton states "I won't let anyone take us backward, deny our economy the benefits of harnessing a clean energy future, or force our children to endure the catastrophe that would result from unchecked climate change." Republican Donald Trump

Donald Trump states "The concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive." References:

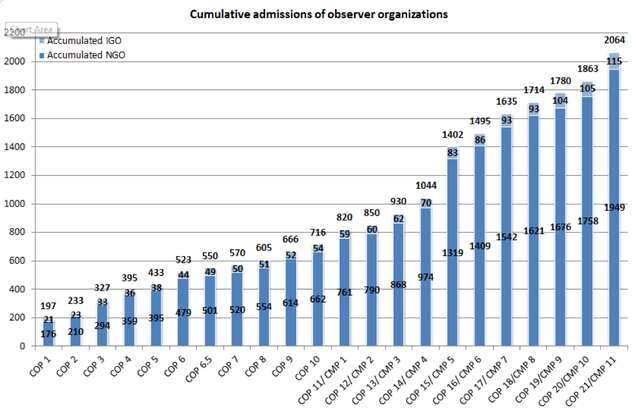

http://www.businessinsider.com/donald-trump-climate-change-global-warming-environment-policies-plans-platforms-2016-10 https://www.hillaryclinton.com/issues/climate/ https://www.donaldjtrump.com/press-releases/an-america-first-energy-plan When I first started learning about the UNFCCC, I thought involvement was primarily from official representatives of countries. I was surprised to learn of the growing involvement of NGOs and other observer organizations. An NGO (non-governmental organization) is a non-profit organization that is independent of the government and can be formed at the local, national, or international level. The number of accumulated NGOs increased from 176 organizations at COP1 to 1,969 organizations at COP21. Who Attends UNFCCC Events? The UNFCCC allows three categories of participants to attend meetings and conferences:

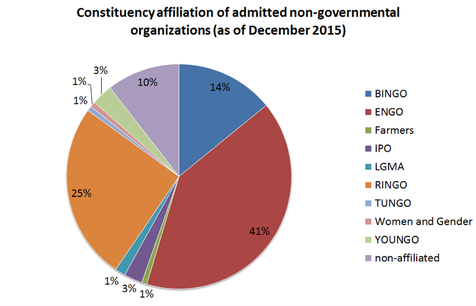

The observer organizations consist of several other categories, notably: non-governmental organizations, intergovernmental organizations, and the United Nations systems and its Specialized Agents.  What NGOs are involved with the UNFCCC? As you can see in the figure displaying the constituency affiliation of NGOs, 41% of NGOs consist of “ENGOs,” or environmental non-governmental organizations. An ENGO specifically focuses on work with the environment, such as depletion of natural resources, species conservation, or climate change mitigation. Here are a few ENGO examples, a subset of the many admitted NGOs at UNFCCC events: 1.WWF The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) was formed in 1961 with the goal to protect Earth’s species and natural places through work with local communities, governments, and other NGOs. The WWF works with the UN and with governments to help ensure that low-carbon emissions are met. They are planning to continue their work again at COP22. 2. Greenpeace International Greenpeace was formed in 1971 to campaign to protect Earth and is now a global campaigning organization that seeks to transform attitudes and beliefs to increase environmental protection. Greenpeace releases position statements for all of the international climate negotiations primarily for policy makers or journalists who want to gain more information about the negotiations. 3. The Nature Conservancy The Nature Conservancy was formed as a nonprofit organization in 1951 and seeks to protect Earth’s lands and waters for both nature and people. The Nature Conservancy helped stakeholders understand the complexities of the Paris Agreement and negotiations at COP21. They are continuing to work to promote climate action and have released statements and blog posts about the negotiations. Why does it matter? Observer organizations, specifically NGOs, have the power to make positive impacts in international climate negotiations. NGOs can increase public awareness through campaigns and education, cultivating a culture of climate awareness and environmental appreciation. Furthermore, NGOs can implement changes in their own organizations or help other organizations make changes to drastically limit their effects on the environment, such as through reduction of green house gas emissions or through ensuring sustainable supply chains. I am looking forward to learning more about NGO involvement in the upcoming negotiations. I will close with sharing a short clip from Earth Hour, the nonprofit created by WWF, to increase global climate action. Here you can see the work being done to amplify the effects of the Paris Agreement, and encourage climate action. Ultimately, every action can make a difference: Sources:

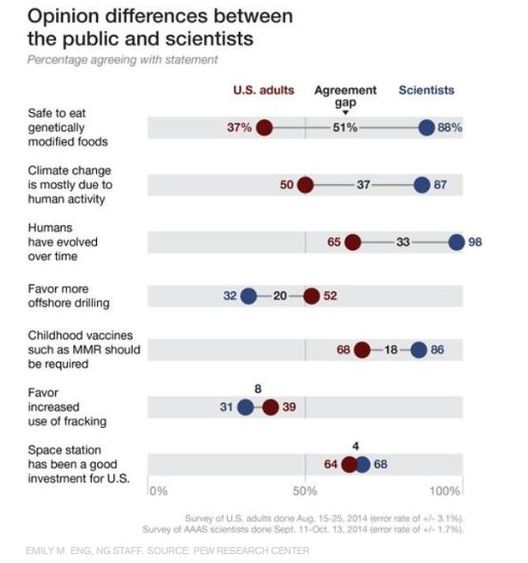

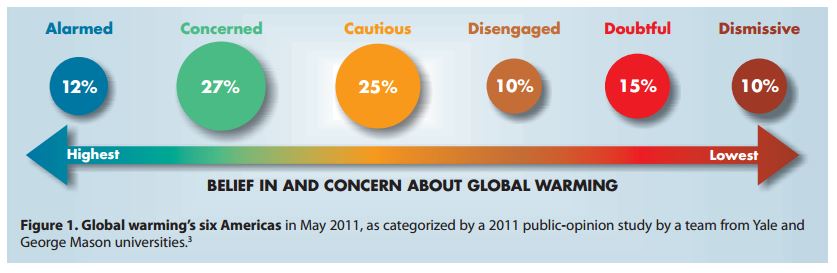

Figures: http://unfccc.int/parties_and_observers/observer_organizations/items/9545.php Observer information: http://unfccc.int/parties_and_observers/observer_organizations/items/9524.php WWF: http://wwf.panda.org/who_we_are/ Greenpeace: http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/about/ The Nature Conservancy: http://www.nature.org/about-us/index.htm?intc=nature.tnav.about Scientists and the public don’t always see things in the same way. In fact, a recent Pew Research Center study identified a significant “agreement gap” for several controversial issues including climate change. While 87% of scientists agreed that climate change is primarily due to human activity, 50% of US adults held the same opinion, an agreement gap of 37%. From GMOs and vaccinations to evolution and climate change, controversy and skepticism towards scientific information seem to be everywhere these days. Regarding climate change, this controversy has dangerous potential. The more politicians perceive (accurately or otherwise) that climate change is not a priority for their constituencies, the less likely they will be to support initiatives to decrease carbon emissions, increase investment in renewable energy, and support other measures to combat a changing climate.  So what do we do to close this gap? Improve scientific literacy! Many may argue that if people have a better understanding of the issues at hand, they would agree with the majority of scientists. However, upon scrutiny, this assertion is oversimplified at best and potentially problematic. Simply throwing more scientific information at the public might not be the best answer for closing the agreement gap between scientists and the public. In fact, work from the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale Law School found that higher levels of science literacy and quantitative reasoning actually increase cultural polarization on issues such as climate change. Work from Dan Kahan and the Cultural Cognition Project identifies identity-protective thinking as the primary problem with science communication, why scientists have so much trouble making their ideas and research heard and understood in the public sphere. While one might assume that the public simply doesn’t know enough about science to understand or interpret scientific risk information, Kahan’s work suggests otherwise. According to identity-protective cognition, “People who are motivated to form perceptions that fit their cultural identities can be expected to use their greater knowledge and technical reasoning facility to help accomplish that—even if it generates erroneous beliefs about societal risks.” Thus, while I certainly do not wish to argue against improving science literacy since that is my primary goal in attending COP 22 as an ACS representative this fall and sharing reflections with my university community, I do agree with Kahan that it is not by any means the cure-all to climate controversy. Scientists need to find ways to communicate without attacking people’s strong held identities and as Kahan would argue… we need more science on science communication to help us figure out how to do just that.

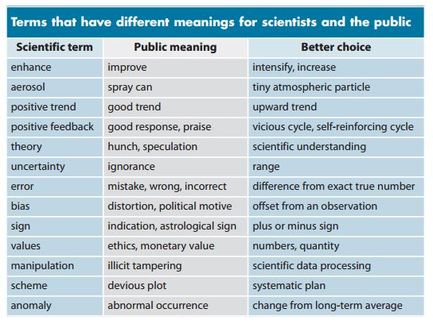

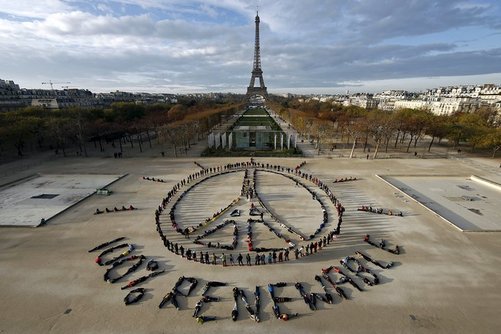

Science literacy is about increasing the scientific knowledge people have access to, but science communication is about how that information is transferred. According to Kahan, people tend to use scientific information not to challenge their thinking, but to support beliefs that have already been shaped by their worldview. As a National Geographic feature article explains, “Science appeals to our rational brain, but our beliefs are motivated largely by emotion, and the biggest motivation is remaining tight with our peers […] We believe in scientific ideas not because we have truly evaluated all the evidence but because we feel an affinity for the scientific community.” So the real question becomes not how can we more effectively spread scientific information, but how can we more effectively cultivate public affinity for science and scientists. How can we cultivate recognition of common humanity capable of mutual understanding despite conflicting worldviews between scientists, non-scientists and everyone in between? Sources: Opinion gap graphic: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/06/150129-public-opinion-aaas-health-education-science/ A nice summary blog post of 2010 cultural cognition research from Kahan: http://www.culturalcognition.net/blog/2012/10/29/the-science-communication-problem-one-good-explanation-four.html 2013 paper from Dan M. Kahan: http://www.culturalcognition.net/browse-papers/making-climate-science-communication-evidence-basedall-the-w.html National Geographic feature: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2015/03/science-doubters/achenbach-text Guest writer Dylan Nehrenberg is a first year medical student at the University of Washington. He graduated from Pacific Lutheran University in May 2016 with a BS in Biochemistry. Dylan participated in PLU's International Honors Program which emphasizes global perspective, discussion, and consideration of the ethical implications of topics discussed. He is from Kent, Washington and plays the violin. From the literary work of George Orwell’s 1984 to the colorblind rhetoric that inhibits proactive discussions of race in Michelle Alexander’s, The New Jim Crow, human language, as the medium for understanding, directs the actions of all persons. But in our century, language has reached a new power. As of 29 August 2016, a new geological epoch has been declared—the Anthropocene—and with it language has become a geologic force. Exxon Mobile should be well-known for its decades-long disinformation campaign against climate change. In fact, it has been argued that Exxon Mobile is solely responsible for the entirety of anti-climate change rhetoric. While for this reason Exxon Mobile has become a symbol of global corruption, I do not think it fair to blame them entirely. We, the general population, but more specifically, the scientific population, are also to blame. While we have sharpened our scientific arguments, accumulated innumerable data, and compiled clever scientific-phrases to argue for the existence of climate change, we have also waged the wrong battle. Exxon Mobile pitched science against language. Language—the framework of every epistemology, the basis of knowledge and understanding, the conduit between world and self—won an easy battle against science. Science lends itself well to only the few, and the language of the forefront scientist rings different bells in the ears of those who have chosen to pursue other fields. A degree of responsibility falls to the scientist, for they must not only learn to communicate with the workings of nature, but with persons as well. In 2011, only 47% of Americans believed that climate change is caused by human activities. This is problematic, for though we recognize ourselves as a geologic force, those who believe that force is destructive are the minority. A publication by Somerville and Hassol attribute this minority to the inability of scientists to “craft simple, clear messages . . . . [and] to put new findings into context.” Somerville and Hassol argue that more public-centered word choice would help communicate the reality of climate change to both media outlets and the public.  Richard C. J. Somerville and Susan Joy Hassol, “Communicating the science of climate change” Richard C. J. Somerville and Susan Joy Hassol, “Communicating the science of climate change” I agree, but new language is not sufficient. The language of climate change often involves discussion of the future, a place in time that is neither absolute nor immediately understandable. Our understanding of the future comes from the past, and so too must our understanding of climate change. Climate change is not an isolated phenomenon. It has an incredible history, linked to social and economic hierarchies of class, wonders of discovery and exploration, and the basic human desire for growth. Climate change was enabled by scientific breakthroughs in the industrial revolution. If we go back, we recognize that theses scientific breakthroughs are a product of class divisions—of a few persons with immense resources and great curiosity. But these divisions weren’t limited to class, there were country divisions as well. The influx of resources from colonialism, which impoverished many countries in order to enrich a few, also laid the necessary framework for the industrialization and subsequent climate change. Those same countries that were colonized—with some exceptions—are the same countries that are now most at risk for climate disaster. These are the same countries which now need their own industrial revolution to join the world economic stage, and have found that the bulk of available carbon to burn has already been sequestered by those imperial powers that had stolen their land. It is in within this rich social and historical context that the language of climate change must be developed, and it will require that the scientist work alongside the English professor, anthropologist, novelist. It is only once we develop a common language that reaches persons in all walks of life, a language that gives them the tools necessary to understand climate change on the level of individual human beings, that we can push back against the decades of linguistic editing endeavored by Exxon Mobile and other members of the disinformation campaign. We must show climate change, beyond science, as it truly is: A shocking, alarming ideological colonization, a continuation of discrimination against those with little, which bargains lives for comfort and benefit. Our affluence is not without context, and so it is our responsibility to develop this new language and to return the privileges with which we’ve been born. We must not let the Sirens of comfortable living draw us to a coast of ignorance and indifference. We must look down and see the throne of past and future bargained lives upon which we sit. Sources: Damian Carrington, "The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced age" https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/29/declare-anthropocene-epoch-experts-urge-geological-congress-human-impact-earth Shannon Hall, "Exxon Knew about Climate Change almost 40 Years Ago" https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/# Richard C. J. Somerville and Susan Joy Hassol, “Communicating the science of climate change” https://www.climatecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Somerville-Hassol-Physics-Today-2011.pdf In December 2015 at COP 21 in Paris, the nations of the world came together with the hopes of forging an agreement to take action on climate change. On the final day of the conference, they formally adopted the landmark Paris Agreement. Since then, 191 nations have become signatories to the Paris Agreement. It will go into force 30 days after its ratification by at least 55 nations accounting for at least 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions. As of October 5, 2016, 74 nations had ratified the Paris Agreement, accounting for 58.82% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This means that it will enter into force on November 4, 2016! The Paris Agreement is different from the Kyoto Protocol in many ways, but two important differences stand out to me. The first is that it includes developing countries—most notably, China and India—who were not required to reduce emissions under the Kyoto Protocol. It also includes the United States who never even ratified the Kyoto Protocol in the first place. The second major difference is that it is not an internationally binding treaty like the Kyoto Protocol, but rather an agreement by member states to put forth their own Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) to fight climate change.

Some key features of the Paris Agreement are:

Two criticisms of the Paris agreement are:

The best analogy I’ve read about the Paris Agreement is that it is like a potluck dinner in which everyone brings what they can to the table. Those who bring a lot are praised and those who bring nothing are shamed. The Paris Agreement is not perfect, but it represents the best chance we’ve got to prevent dangerous warming of our planet. Now it’s time for us to hold our elected officials accountable to their promises and demand action. Sources: The Paris Agreement. http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php (Accessed Oct 6, 2016) |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed