|

From humans to climate change and everything in between, everything has a tipping point at some point in time. What exactly is someone or something’s tipping point, though? The tipping point is “the point at which a series of small changes or incidents becomes significant enough to cause a larger, more important change.” (1) In relation to climate change and climatology the tipping point “occurs when the climate system is forced to cross some threshold, triggering a translation to a new state at a rate determined by the climate system itself and faster than the cause, these changes would produce impacts at a rate and intensity far greater than slow and steady changes currently being observed (and in some cases, planned for) in the climate system. These changes would also become irreversible to some point after being triggered.” (2) The idea of the tipping point described by the IPCC is said to be able to cause “major or abrupt climate changes” which could cause substantial disruptions in human and natural systems Specifically, the systems that the IPCC include that would be disrupted are:

The importance of the tipping point and its recent significance as we try to combat climate change has caused a lot of countries to take action in playing a role to prevent us from approaching the threshold. Three weeks ago both China and The United States formally joined the Paris Agreement. The Paris agreement calls for “a global action plan to put the world on track to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2°C.”(3) This is momentous since China and the U.S. together are responsible for over 38 percent of global emissions. (4)

Will these recent actions help? This quick entry into applying the Paris Agreement into country policies is very critical because reducing emissions early-on and intensively is one of the most effective methods to preventing catastrophic climate change impacts. 1) Dictionary.com 2) https://climate.dot.gov/about/overview/climate_tipping_points.html 3) http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/international/negotiations/paris/index_en.htm 4) http://www.triplepundit.com/2016/09/tipping-balance-u-s-china-ratify-paris-agreement/

0 Comments

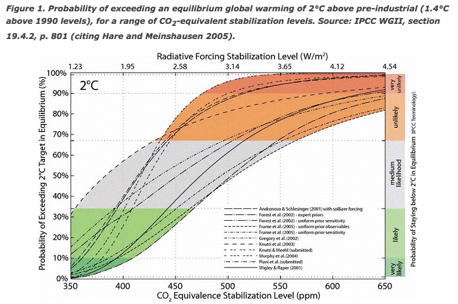

Last year, in the Paris Agreement the world’s nations agreed at COP 21 to do their best to limit global temperature increase to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. The origins of this number can be traced back to 1992 with the signing of a treaty agreeing “to prevent dangerous interference with the earth’s climate.” Soon after, scientists began coming up with numbers close to 2°C. Eventually, this number was adopted by the European Union, the United States, and other industrialized countries in 2009 before COP 15 in Copenhagen. However, there is a lot more hiding behind the 2°C mark than meets the eye. For starters, the emissions targets laid out for each country in the Paris Agreement are not sufficient to keep the global temperature increase below 2°C. When the number 2°C was adopted in 2009 many countries (mainly African) were furious. In the words of Sudanese chair Mr. Lumumba Di-Aping, “Two degrees is a certain death for Africa.” Industrialized countries came up with 2°C because in their minds, that was preventing a “dangerous” level of climate interference. For them? Maybe. For African and small island countries? Not so much.  Black Lives Matter protesters at COP 21 in Paris http://app.greenamerica.org/climate-justice/images/hero/blm-paris-4.jpg Black Lives Matter protesters at COP 21 in Paris http://app.greenamerica.org/climate-justice/images/hero/blm-paris-4.jpg Studies have shown that a global temperature increase of 2°C would cause sub-Saharan Africa to lose 40-80% of cropland due to drought by 2040. Small island nations like the Marshall Islands would also be devastated by an increase of 2°C because of rising sea levels. Before COP 21 last year the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands stated “We cannot be expected to sign off on a small island death warrant here in Paris” in reference to the 2°C mark. The Paris Agreement contains one line about a “reach” target of 1.5°C that small island nations fought hard to include. It states as a main goal to hold “the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change." However, the 1.5°C mark is not legally binding, and was most likely included as a way to recognize the very real concerns of African and small island nations. Simply recognizing their concerns isn’t enough. The Paris Agreement shows that the world has agreed that any global temperature increase over 2°C is a dangerous level of interference with the climate. This is true. It is also true that 2°C will be fatal for many people in African and small island nations. What does our acceptance of the Paris Agreement say about the value we place on the lives of these people, who are mostly people of color? If we truly placed an equal value on each human being’s life, then the goal of limiting global temperature increase to 2°C is morally unacceptable. In her article “Why #BlackLivesMatter Should Transform the Climate Debate,” Naomi Klein writes, “If we refuse to speak frankly about the intersection of race and climate change, we can be sure that racism will continue to inform how the governments of industrialized countries respond to this existential crisis.” If black lives in Africa mattered, we would have agreed on a stricter goal than 2°C years ago. #BlackLivesMatter does not mean that black lives matter more than other lives. It points out the numerous examples where black lives are not valued the same as white lives and are subject to systemic racism. Decades of climate inaction finally culminating in the Paris Agreement is yet another example of this. If we look at the Paris Agreement through the lens of #BlackLivesMatter, we can see that there is a need for a fundamental shift in the way we think about international agreements for fighting climate change. By all means, we should celebrate that some sort of agreement was reached at COP 21 in Paris. However, it is equally important to recognize that it is not enough for people of color around the world. With the election coming up in November, it is always important to consider politician's view on climate change when casting a vote. The young generation is beginning to learn about politics and deciding between becoming a democrat or a republican. Keeping the young involved is very important to act on the issues of climate change. Many people believe we are not truly aware of what is happening within or community, but that is false. In 2013 a climate change survey was conducted of 1000 students, concluding 70% of students were very concerned or fairly concerned about this worldwide issue. The British Science Association also conducted a survey showing about 63% of 18-24 year-old's have expressed high concern when relating to climate change. Professors and teachers in local high schools are bringing climate change more to classrooms to promote awareness. The video below shows how politicians have been viewing climate change. Although voting solely based on climate change is not ideal, it is very important to consider. Voting for a candidate who believes the issue is over funded or a conspiracy will cause the world to sink quick. In the 2014 election, 19.9% of the 18-24 year-old's have voted. Almost 20% of the voting population consists of the young, making it very crucial to keep the young generation involved. YouGov found 55% of the 18-24 year-old's agreed that the flooding in the UK was because of climate change. Having over half of the age group aware that climate change is real and increasing is imperative. Encouraging this age group to vote based upon climate change needs to start happening. Expressing concern as a group will be more effective when changing an issue worldwide, especially an extreme one, such as climate change. References:

http://civicyouth.org/quick-facts/youth-voting/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6J0FlkNdMio&feature=youtu.be http://www.climateaccess.org/sites/default/files/COIN_Young%20Voices.pdf  Last week I read an article in the New York Times entitled “That Cute Whale You Clicked On? It’s Doomed”. The author, Amanda Hess, writes about wildlife photographers using Instagram as a way to increase environmental awareness. They send a strong message on the reality of climate change by baiting viewers with a cute animal picture and pairing it with a description of how said animal is threatened. It’s environmental education, Instagram-style. Hess’s piece focuses predominantly on wildlife photographers as activists on social media, but I think anyone can do this: from college student to conservation biologist. It’s natural that photographers should be the first to adapt to this new platform to activism. Instagram is inherently visual and encourages an artistic lens. Social media can be overwhelming if you are new to it, and at times it seems downright trivial (think the “Damn, Daniel” phase). Yet it remains a powerful platform for driving change today. Visibility is the first step in triggering engagement in a social movement. Bringing issues such as biodiversity and habitat loss into the limelight is the first step toward influencing their future behavior. How will people put their money and votes behind an initiative to protect a wetlands area if they’ve never experienced the wonder of the wildlife there? Instagram is a fantastic platform for bringing inaccessible issues to the top of the public’s newsfeed. It’s easy to throw a like to a cute penguin you see on Instagram, and if you take thirty seconds to read the caption you might learn about the impacts of rising sea temperatures on Mr. Penguin’s life. Unlike that boring video about melting ice caps you watched in tenth grade bio, this lesson is short and sweet. You’re more likely to remember it. Climate change is a vast and complicated issue. It affects human health, crop production, ecosystem functions, coral reefs, economics, and international relations, as I touched on in my last blog post. As I write those terms, however, it’s glaringly obvious to me that they mean very little without a context. People are not swayed by large, scary proclamations. It’s hard to decipher the wordy warnings and analysis published by scientists. A heart-jerking image is enough to get them reading, to get them interested in learning more about how climate change is impacting the world around them. A shining example of the power of photography? Ansel Adams. You’ve probably seen his work even if you don’t know his name. Adams is known for his striking photos of the American wilderness. Working with Nancy Newhall in the 1950s and 1960s, he helped create the Sierra Club’s This is the American Earth (1960), a book which is considered key in launching the first widely-embraced citizen environmental movement. Adams fought for the Wilderness Act and preservation of our country’s natural spaces. In many ways he is a founding father of our National Park System. While we aren’t all Ansel Adams, most of us do at least have Instagram. Take a few moments to go find the future Ansel Adams out there and throw ‘em some love. Here are a few ways you can make your Insta-use a bit more conscientious. Stay educated. Be up to date on the latest environmental news. Exciting things are always happening, like Obama’s creation of the first marine monument in the Atlantic. Add a few reliable news sources or nature-themed accounts to your homepage--celebrate landmarks like the National Park Service’s centennial this year. National Geographic has a great newsfeed to keep you up-to-date on all things nature. Share with a purpose. Arctic animals are cute, but focus on something closer to home now and again. I follow the West Michigan Environmental Action Council (WMEAC), a nonprofit I interned at two years ago. Based out of Grand Rapids (Midwest represent!) they work to involve the West Michigan community in environmental stewardship. Even though I go to school in Baltimore, MD now, I love seeing them host cleanups like this one. If you like something in your area, or share their information on other social media, your friends will probably like it, too. (I always steal or cool accounts from my friends.) Support climate-positive brands. @Waterlust is a beautiful account that raises awareness about global water issues through social media. Their posts are educational and full of #travelgoals. Click on hyperlinks when you like an account: by visiting a brand’s website, you are showing them virtual support, and they can attract more donors/ad buyers by showing that their Instas lead to click conversions. These are just a few of the ways you can flex your Instagram muscles in support of climate change awareness. There are hundreds of cool accounts and interesting themes to be found on social media--go explore what’s share-worthy. Know of some awesome environmental accounts? Share ‘em in the comments below! Katherine Jesser: The Importance of Forests and Forest Resources in a Time of Climate Change16/9/2016  Katherine is a senior at the University of Washington majoring in Environmental Science and Resource Management with a focus in Wildlife Management and minoring in Marine Biology. She is from Eugene, Oregon and plays trombone in the Husky Marching Band. Forests around the world cover 4 billion hectares of land, that’s 30% of the earth’s surface (Kirilenko 2004)! Forests act as the lungs of the Earth by turning the greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, into oxygen and sugars with help from the sun. This chemical process allows the trees to store this carbon for hundreds of years until they die and decompose (Kirilenko 2004). Trees can be made into biofuels, which could decrease our dependence on fossil fuels and other non-renewable energy sources. At the same time this could decrease the biodiversity and natural functionality of the forests (Righelato 2007). Trees are of course, used for building materials, paper and other widely used products. Deforestation is a major problem in countries like Brazil and Indonesia where it is occurring at alarming rates compromising the positive effects that forests have on our climate. Trees are truly an important resource and provide many ecosystem services  This summer I interned at the Olympic Natural Resources Center in Forks, WA near the Olympic National Park through the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forestry Sciences. During this 3-month internship I collected understory vegetation data for a Long Term Ecosystem Productivity study being carried out in Sappho, WA. This study was started in 1994 and includes institutions and agencies such as the University of Washington, Western Washington University, Washington Department of Natural Resources (WA DNR), and the US Forest Service. I worked mostly with WA DNR employees. I learned from them how private and public logging in Washington has changed in recent years to promote sustainability and ecosystem health while selling the timber on the state trust lands. This study is unique because of its multiple sites in Washington and Oregon, and its longevity. The study is planned to last for 200 years, presenting an excellent opportunity to explore long-term changes in the forests that are being studied. The manipulated variables in the study include the age and species of trees, and amount of woody debris left after cutting. These components are very important in the functionality and roles of a forest within its ecosystem as well as to the adaptability of forests to climate change. Different treatments included selective thinning of older trees to create old growth habitat, planting earlier successional species or using the plantation style planting of Douglas-fir used by most commercial loggers. Earlier successional stands with alder are able to fix atmospheric nitrogen and improve the nutrition of the soil decreasing the need for fertilizers. Some understory species, such as salal, have deep root systems and can break down rock parent material increasing the amount of soils. Longer lived tree species such as Sitka spruce and Douglas-fir have shallow root systems and do not fix nitrogen, but do provide excellent habitat for animals that require old growth forests such as the marbled murrlet. All of these different stages of forest have their benefits and a goal of the Long Term Ecosystem Productivity Study is to see how these treatments react to changing conditions and climate change, while also preserving the natural resources we need for our society. Maintaining biodiversity, different age classes and types of species will allow scientists and managers to have a better chance of keeping our forests intact at some level (Bormann 1999). With less rain, higher temperatures and more forest fires (Bormann 1999) in the Pacific Northwest these systems may react differently and by knowing how, forest managers will be able to better protect habitat and resources. Everyone in the business of trees and natural resources are trying to answer the question: what is the best way to manage this ecosystem? However, those stakeholders involved all want what is best for their sets of needs and goals, which leads to conflicts of interest. Managing a forest for lumber, fish and wildlife habitat, recreation and carbon sequestration can prove difficult with so many agencies and private interests involved. As climate change continues worldwide, forest management will be at the forefront of environmental science and resource management discussion. The national and international trade of timber products is affected by, and in turn influences, climate change. If scientists, forest managers and citizens can work together to better protect our forests and help them adapt to climate change, then perhaps this resource can be sustained for future generations. Sources

Bormann, B.T., J.R. Martin, F.H. Wagner, G. Wood, J. Alegria, P.G. Cunningham, M.H. Brookes, P. Friesema, J. Berg, and J. Henshaw. 1999. Adaptive management. Pages 505-534 in: N.C. Johnson, A.J. Malk, W. Sexton, and R. Szaro (eds.) Ecological Stewardship: A common reference for ecosystem management. Elsevier, Amsterdam. Climate Change and Food Security Special Feature – Research Articles – Biological Sciences – Sustainability Science: Andrei P. Kirilenko and Roger A. Sedjo, Climate Change impacts on forestry PNAS 2007 104 (50) 19697-19702; published ahead of print December 6, 2007, doi:10.1073/pnas.0701424104 Righelato, R., & Spracklen, D. V. (2007). ENVIRONMENT: Carbon Mitigation by Biofuels or by Saving and Restoring Forests? Science, 317(5840), 902-902. doi:10.1126/science.1141361 Image 1: National Science Foundation Image 2: Photo taken by Courtney Bobsin Image 3: Sustainable Forestry Initiative In the United Nations Framework On Climate Change, written in 1992, the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” is introduced. In the context of the UNFCCC, this principle addresses the reality that though individual parties share a vision to mitigate climate change and stabilize greenhouse gas emissions, there are social and economic factors that influence each party’s ability to contribute to the effort. Historically, developed countries have emitted more greenhouse gases as technology, business, and infrastructure stabilized their economies. Developing countries, however, are still in the process of strengthening their economies and have fewer financial resources to devote to sustainable development in the coming years.

To gain a better understanding of the complex issues of common but differentiated responsibilities, I want to introduce the financial responsibilities of UNFCCC parties and some of the financial mechanisms in place to support the most vulnerable parties. The UNFCCC separates countries into three different groups based on commitments and responsibilities[i]:

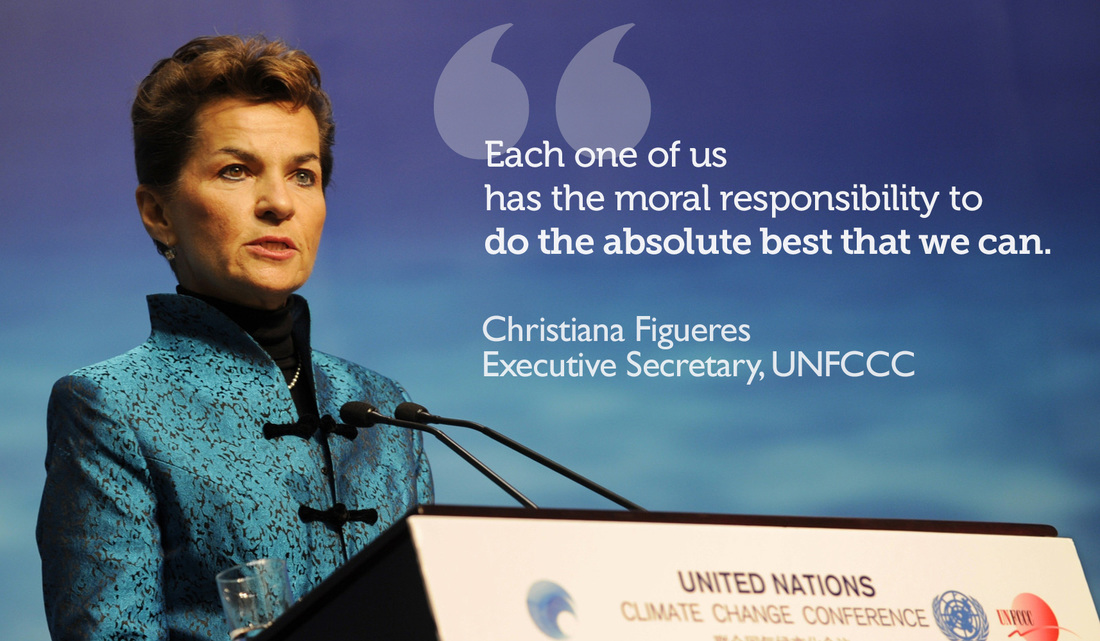

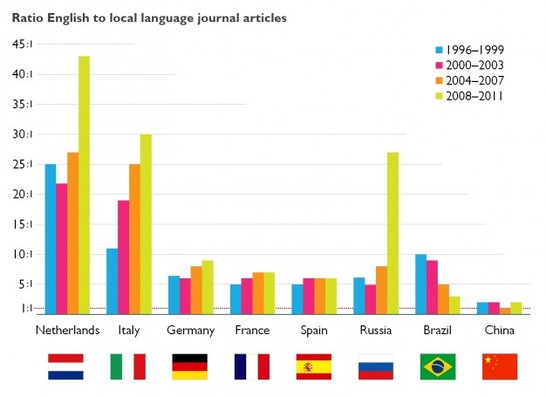

A financial mechanism was developed by UNFCCC so that Annex II parties can assist developing countries in both the mitigation and adaptation of climate change. A portion of the financial mechanism was given to the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) and also to the Green Climate Fund (GCF)[ii]. GEF was established in 1992 and currently works with partners, such as the United Nations, to assist in solving the most challenging environmental problems[iii]. Currently, GEF has 4,407 projects and 16.22 billion dollars of grant funding[iv]. GCF was established by the United Nations at COP16 in 2010[v]. This global initiative seeks to support developing and highly vulnerable countries limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions and has raised over 10 billion dollars[vi]. Though a financial mechanism is in place, the complexities of financial responsibility at UNFCCC raise many questions: Should developed countries, who have contributed to the majority of human-induced climate change, be responsible for paying for future development in developing countries? How do we account for historical emissions before there were records from individual countries? Should developing countries be expected to have the same emission rate reductions as developed countries when they make lack the technology, infrastructure, and financial means to make sustainable development possible? Ultimately, questions of justice and equity play a major role in determining financial responsibility at UNFCCC. Though there may not be immediate answers, it is critical that we continue bringing these questions to the forefront of the decision-making process. Highly vulnerable countries should not be alone in the effort to mitigate and adapt to climate change. We share a common goal, and together we have the potential to use our differences to find the best environmental solutions. Sources: [i] http://unfccc.int/parties_and_observers/items/2704.php [ii] http://unfccc.int/cooperation_and_support/financial_mechanism/items/2807.php [iii] http://www.thegef.org/about-us [iv] http://www.thegef.org/about-us [v] http://www.greenclimate.fund/the-fund/the-big-picture#history [vi] http://www.greenclimate.fund/the-fund/behind-the-fund Image:https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/10-people-who-care-about-climate-change-more-than-your-average-politician In the process of applying to be an ACS delegate at COP22, I found myself on the official COP22 YouTube channel looking to learn as much as possible about UN Climate Change Conference proceedings before completing my application. Back in June, I clicked on this one, only to realize I was unable to understand a single word. This speech by Her Royal Highness Princess Lala Hasnaa of the Kingdom of Morocco is, of course, in Arabic, the official language of Morocco. While I had a moment of frustration that there were no English subtitles, I also understood that it was silly for me to assume a speech for an international conference would be in English. Language diversity should certainly be both expected and valued in international relations. While not necessarily apparent to those engaged with UN proceedings via English-speaking media outlets, social media and other digital communications display the multilingualism of UN proceedings. Since June, the COP22 steering committee launched their official communications campaign starting August 1st. This campaign included a short video titled “Just open your eyes,” which highlights the natural resources of Morocco and the importance of sustaining them. This video is available in classical and dialectal Arabic, dialects of Berber, French, English and Spanish.  COP22 Facebook cover graphic COP22 Facebook cover graphic Language diversity is notable at COP22, the first COP to communicate in four of the UN’s six official languages. Official materials are communicated in Arabic, French, English and Spanish. While multilingual communication is evident in official conference branding and materials on their website, posts to their Facebook and Twitter accounts are primarily in Arabic and French (ce que je peux lire, heureusement). Arabic is the official language of Morocco along with Tamazight, a Berber language. In addition, French is often the language of business and diplomacy due to colonial influences in Northwest Africa. Equitable language representation is important in international diplomacy. Mutual understanding is absolutely essential when concerning agreements between nations, especially when the number of nations represented is nearly 100… which is the case at COP 22. Furthermore, the more languages in which UN proceedings are available, the more everyday people can, at least in theory, have access to this information. However, the logistics of communicating in more than one language can make things complicated, translation is never perfect and there is usually some trade off between language diversity and mutual comprehensibility. Of particular interest to me at COP 22 is the importance not only of multilingual communication, but multilingual communication of science. While studying in Windhoek, Namibia my junior year of college, I became interested in the dynamics of language in science education. While the official language of Namibia is English (as in many African countries since the colonial era), most of the university students and professors I interacted with spoke it as a second, third, or even seventh language. During a lab session I overheard a debate between several students regarding whether introductory science courses should be taught in English, to prepare students for the heavy focus on English in higher science education or in native languages, so students would have stronger understanding of the concepts. Since English is the language of professional science to such a high degree, it is clear why schools may choose to emphasize English in their science courses. But what does this mean for nonnative speakers? What does this mean for science and its place in the world? A similar debate exists for international negotiations. Is it better to choose one language for all negotiations, maybe a neutral language such as Esperanto (created in 1887 as a neutral, combination of European languages), or to communicate in all languages? How does language diversity affect the efficacy of international policy and debate? This COP is already reputed to be the COP of action, where global leaders move from lofty ideals and vague goals to concrete plans. While the Paris Agreement received much media fanfare, Morocco must be the time when actions begin to come into place including funding and further logistics. The support of actions to combat a changing global climate will require communication and outreach in many global languages. As we approach COP22, I am particularly interested by how language diversity is both encouraged and limited in international debate. How does language diversity affect international relations? How does the dominance of English in science affect global science literacy and how does science literacy affect the course of international policy? Sources:

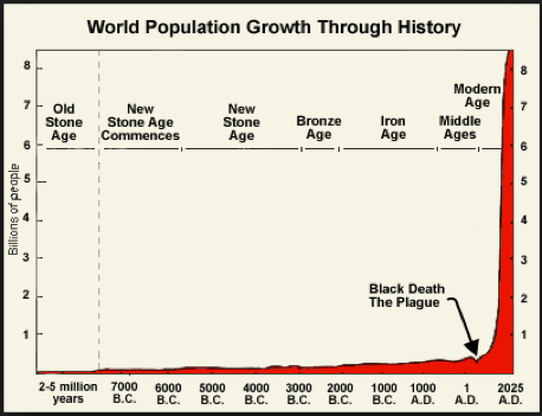

Speech from SAR Lala Hassna: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXvCcQSw0Sg Language Priviledge: https://linguisticpulse.com/2013/06/26/language-privilege-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters/ COP22 Launches Communications campaign: http://www.cop22.ma/en/cop22-launches-communications-campaign-raise-awareness-climate-change COP Digital Communications: http://www.cop22.ma/en/cop22-digital-communications UN Official Languages: http://www.un.org/en/sections/about-un/official-languages/ English in Science: https://www.researchtrends.com/issue-31-november-2012/the-language-of-future-scientific-communication/ COP22 and action: http://cop22.ma/en/cop22-roadmap-devoted-action The idea of The Commons was originally formulated as an economics theory written by Victorian economist William Forster Lloyd in 1833, but the idea progressively became known as the idea of the tragedy of the commons through Garrett Hardin’s influential 1968 essay regarding overpopulation. Hardin’s essay described the tragedy of the commons as a shared resource system (“commons”) where the tragedy became an individual’s driving force behind their inherent selfishness, pushing them to utilize the commons to their own greatest benefit and according to their own self-interest rather than think of the inevitable unintended and undesired consequences of their own actions amongst the community. The theory rationalizes that “as the demand for the resource overwhelms the supply, every individual who consumes an additional unit directly harms others who can no longer enjoy the benefits. Generally, the resource of interest is easily available to all individuals; the tragedy of the commons occurs when individuals neglect the well-being of society in the pursuit of personal gain.” {Source 2-5} Hardin’s essay has become influential with the recent problem of overpopulation. In the last five-hundred years alone, the population has been growing at a nearly exponential rate (Figure 1). The tragedy of the commons is often cited in connection with an attempt at creating sustainable developments. It has posed the possibility of uniting economic growth with environmental protection but has also brought recent debates over global warming and climate change into the picture. The overpopulation issue also brings along a myriad of other uncertainties regarding some of the shared commons (i.e the atmosphere, oceans, land, agricultural space, water, food, and shelter.) {Source 2-5} Through Hardin’s 1968 Essay we must construct some overarching conclusions which can potentially help our current “Commons” Problem.

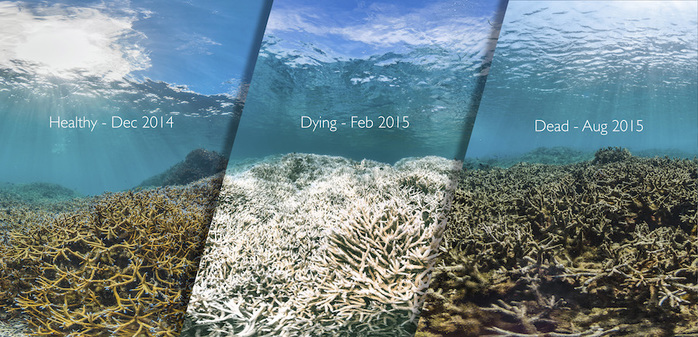

1. The world is biophysically finite, meaning that as the population continues to grow, the resource pool decreases per capita. There will be fewer resources that each person must share. Ideally, humans must learn to “both stabilize population, and make hard choices about which ‘goods’ are to be sought.” {Source 1} 2. Overpopulation is one of the biggest examples of the tragedy of the commons, with the earth being our “commonly-held ‘pool’.” Hardin's gloomy assumption of human’s inherent selfishness and self- centered rationale could lead to two potential outcomes. One of these outcomes is self-realization, which will lead those who hold this mentality to think that we must act in a more selfless manner. The other outcome is indifference, which will lead those who hold this mentality to think that we are only here to exploit the commons. Hardin states that neither a utilitarian ideology nor a laissez-faire system solves overpopulation, but we could instead look at the argument of utilitarianism. Under utilitarianism, it is understood that overpopulation will always be counterproductive in this current day and age without current population size and work to combat over-population in a way where the maxim “the greatest good for the greatest people” becomes the greatest good for current and future peoples. {Source 1} 3. “The ‘commons’ system for breeding must be abandoned,” and something must be enforced to restrain individual reproduction to a certain extent. Decreasing reproduction through individual conscience is the ideal in creating fewer people whose conscience is set in appealing the overall population, and the earth. This current population must realize that “sacrificing freedom to breed will obtain for us other more important freedoms which will otherwise be lost” later on for ourselves or for our children. {Source 1} 4. The biggest problem we are facing is gaining peoples' consent to a system of coercion for combatting these current overpopulation issues. “People will only consent if they understand the dire consequences of letting the population growth rate be set only by each individuals' choices”. Each of Hardin’s proposed problems regarding the tragedy of the commons have great potential outcomes, but we must all work together to work on our shared “Commons” together by protecting this planet and our home. Source 1: http://faculty.wwu.edu/gmyers/esssa/Hardin.html Source 2: http://tragedy.sdsu.edu/ Source 3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tragedy_of_the_commons Source 4: http://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/tragedy-of-the-commons.asp Source 5: http://www.academia.edu/9761177/Utilitarianism_and_The_Tragedy_of_the_Commons Source 6: http://www.susps.org/overview/numbers.html Climate change has disturbed many living creatures throughout the world and coral reefs just happen to be included in that range. Warmer air has caused the ocean water temperature to rise, creating an unstable environment for the corals to live in. Corals are very sensitive to the water change and if the temperature stays above normal for a period of time, the corals begin to lose food that was stored in their tissues, this is called zooxanthellae. Zooxanthellae supply glucose, glycerol, and amino acids for the coral and are critical for maintaining a healthy state of living. Corals use glucose, glycerol, and amino acids for producing calcium carbonate, fats, carbohydrates and proteins, which are essential. The zooxanthellae contribute to the beautiful colors of the corals. Losing quantities of zooxanthellae will cause the coral to bleach, resulting in weakness and prone to diseases. When the coral has lost all zooxanthellae, it can no longer survive, resulting in death. Due to more carbon dioxide being released the ocean pH is becoming more acidic throughout the world. Since 1800, it is known that oceans have absorbed about 1/3 of the carbon dioxide from human activity and another 1/2 from the burning of fossil fuels. Corals cannot absorb calcium carbonate when the pH is lower than normal, causing their skeleton weaken and eventually dissolve right into the ocean salt water. Rising pH levels are not only going to affect coral reefs, but all organisms that live in the ocean. Organisms such as snails, clams, and urchins also make calcium carbonate so they will be affected. The ocean population will be more prone to disease because of the high acidity breaking down immunity. This can be a huge threat to both the organisms that live in and out of the oceans. Based on the image above, coral is being greatly affected quickly by the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. Corals provide food and shelter for many organisms that live within them, and without the corals, many fish and sea creatures will be left without it. Although coral seems to not have a huge impact on our society, it really does when you learn what it provides and how it is used in an ecosystem.

References: Corals. (n.d.). Retrieved September 02, 2016, from http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/corals/coral02_zooxanthellae.html Coral Reefs and Climate Change - How does climate change affect coral reefs - Teach Ocean Science. (n.d.). Retrieved September 02, 2016, from http://www.teachoceanscience.net/teaching_resources/education_modules/coral_reefs_and_climate_change/how_does_climate_change_affect_coral_reefs/ |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed