|

Stevie Fawcett

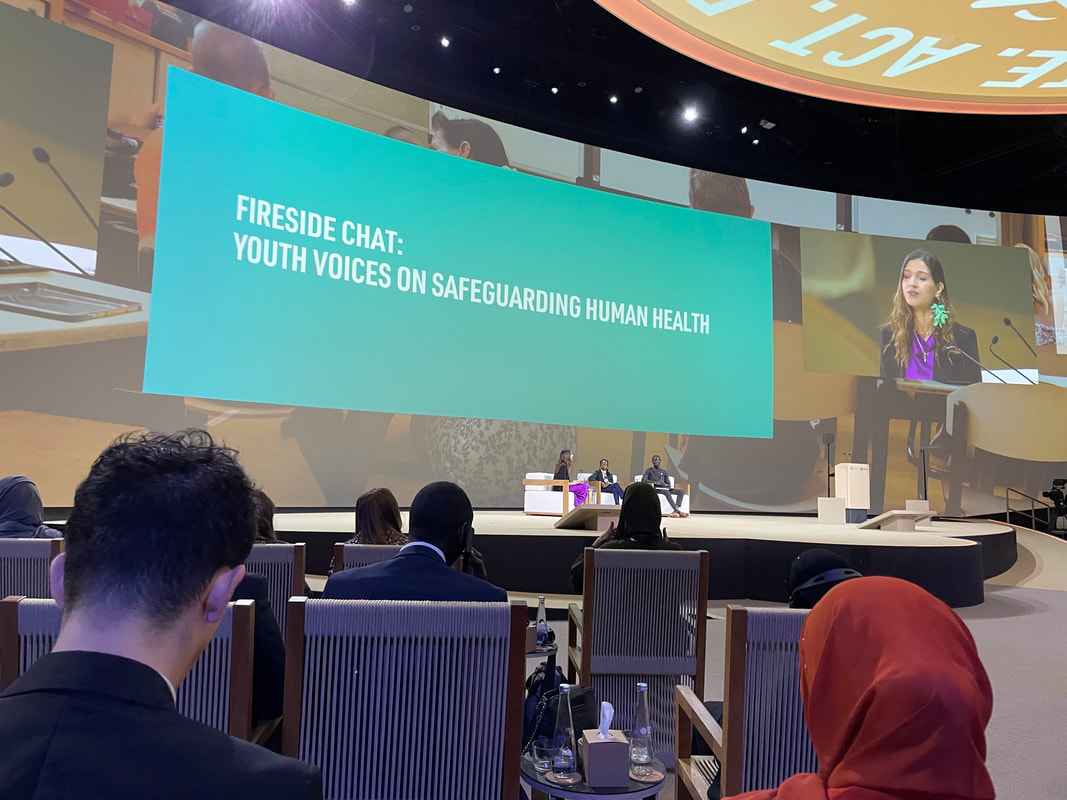

[email protected] For the first time ever, public health took center stage at a COP conference during COP28’s Health Day on December 3rd, 2023. Announcements made during Health Day included a one-billion-dollar commitment toward climate health, which seeks to prioritize health benefits of the people most affected by climate change. These funds are meant to support the Declaration of Climate and Health (1), which calls for action toward adaption and resilience related to climate health. This declaration, which has been signed by 148 countries, represents the most significant document from a COP conference that recognizes the importance of health in the context of climate change. This declaration outlines the integration of health into the climate strategies of each of the signing countries, including specific actions meant to be taken by each country. For the United States, the committed goals included decarbonization of the health sector and improving medical assistance to other countries in responding to health crises related to climate change. Beyond the discussions and announcements put forth during Health Day, COP28 also provided a platform for scientists and health workers to speak about how health is impacted by climate change in different parts of the world. These conversations went beyond the health issues I was personally aware of prior to my attending at COP28, and speak to the immensity of issues that stem from climate change. Below, I have highlighted some of the most significant topics that did not receive as much attention during Health Day. Mental Health: Many people, especially youth, commonly experience intense anxiety and stress in response to climate change. These stressors are also more likely to compound over time in underserved populations, as youth are more likely to experience traumatic events during development, such as forced relocation or the disruption of nature-based livelihoods. In indigenous populations, the destruction of nature caused by climate change can also destroy one’s sense of cultural identity. This has a huge impact on suicide rates and general mental health in indigenous communities. The mental health of climate leaders is also an important topic that is often neglected. These leaders experience an intense amount of stress and anxiety around their work, which can negatively impact productivity and happiness. Climate Change in Medical Schools: The production of fossil fuels not only alters the natural environment, but also increases risks of several diseases. Therefore, in the medical field, the production of fossil fuels is self-sabotage. This concept is central to climate health and has garnered significant support from students and staff at medical schools around the world. Many of the health leaders at COP28 are looking to incorporate climate health into the curriculum of medical schools, which in turn should teach the future doctors of the world important strategies to treating climate-related disease and decarbonizing medical practices. Educating the Public: The dangers of climate-related diseases are increasing, but not everybody knows this. Yet another facet to climate health is the ability to inform the public of the risks associated with climate change in the context of public health. Education also looks drastically different in different areas of the world. For instance, disease-carrying mosquitos are an important topic in the global south, while countries such as the United States may want to focus on the health impacts of natural disasters like wildfires and floods. 1 - https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/climate-change/cop28/cop28-uae-climate-and-health-declaration.pdf?sfvrsn=2c6eed5a_3&download=true

0 Comments

By: Cailey Carpenter For two weeks in Dubai, there was a fiery energy that emanated from every square inch of the Convention Center. With each passing day, I could feel the pressure mounting on decision makers at COP28. But this sense of urgency wasn’t just contained to the decision makers. Tired of standing on the sidelines of countries’ frustrating acts of self-interest, youth and interest groups made their presence known at COP28. These activists didn’t shy away from protests despite the ‘shocking level of censorship’ of the UAE presidency. One protest in particular caught my eye: Not only did I find this activism a bold move in a country that produces 3.2 million barrels of petroleum products per day, I was taken by surprise when reading the sign entitled “NO CCS!”, CCS being shorthand for Carbon Capture and Storage. This was not an isolated event – messages against CCS ran rampant throughout COP28. Why would we oppose the our most promising method to remove carbon from our atmosphere? This is our hope at a net-negative carbon economy, and arguably, a key component of reaching net-zero carbon emissions in a reasonable time frame to combat the major effects of climate change. I understand the sentiment that CCS is a way by which big oil producers can avoid accountability for their actions by pushing the responsibility of emissions to CCS technologies/companies. It is true that avoiding a phase out of fossil fuels expecting a scale-up of CCS is an irresponsible and unsustainable solution. However, I don’t think this is a reason to completely discount CCS as a viable climate solution. CCS is often a controversial topic because many don’t understand the relative weight of the risks and benefits, so I found the blind rejection of CCS at COP28 troubling. This post aims to clarify the prospects of carbon capture and storage (CCS) for mitigating climate change.

The truth is: CCS technology is not as robust as we’d like it to be as a large-scale decarbonization solution. There are still major issues we need to deal with before implementing CCS worldwide – challenges that are scientific, engineering, and political in nature. In 2023, the IPCC estimated that even if CCS is deployed at current full capacity, it will only make up 2.4% of global climate mitigation strategy. Many of the promising CCS projects have either stalled or shut down. Selecting a location with the correct geochemical makeup for long-term storage is difficult. Monitoring CO2 capture and storage has its challenges because we can’t directly see a mile below ground where these plants often operate. But most of all, CCS is expensive with few direct benefits to the operator. CCS operations are estimated to cost $20-110 per metric ton of CO2 stored. The use of fossil fuels leads to emissions of 34 billion metric tons per year, so this adds up quickly. On top of this, what’s to gain from CCS beyond the common good? There is no financial incentive to set up and maintain a CCS project, and CCS comes with liabilities. Monitoring of CO2 remains a challenge, making leaks difficult to detect. If CO2 does leak out, the blame and disdain is directed towards the owners. Furthermore, there is ongoing debate among scientists as to whether pumping CO2 underground can increase seismic activity and trigger earthquakes, something world leaders aren’t willing to risk on behalf of disapproving populations. CCS cannot succeed without further innovation, and most importantly, regulation. Regulation on a global scale is a difficult endeavor, which is why COP is critical for achieving our climate targets. In my eyes, COP is a place where no climate solutions should be off-limits. COP shouldn’t end in empty promises; leaders must negotiate towards a plan of action that is feasible for all parties, even if this includes unconventional methods. Science and engineering innovation work quicker than negotiating policies, so the technical challenges should not be the limiting factor. We need to accelerate climate change mitigation more than ever, and CCS may play a key part in this. This leads us back to the statement that started this all: “NO CCS!”. While I agree with the message that CCS is not a means for fossil fuel producers to evade responsibilities for their significant contributions to the climate crisis, I believe this language can easily be interpreted in a way that perpetuates misinformation. The public can be easily influenced, so it is of vital importance for scientists and climate activists to be cognizant of the way they portray their arguments in order to avoid unintended (and possibly dangerous) side products of their good intentions. Where were all the carbon scientists at COP? Two and a half months ago, I headed to COP28 as a budding chemist, eager to explore the sustainable technologies being developed to fight the climate crisis. Day 1 got off to an auspicious start: In the Green Zone, my cohort and I quickly zeroed in on a group promoting Dubai’s planned implementation of a massive concentrated solar power plant by 2030. The sales pitch was wonderful, but as scientists, we were anxious to learn the underlying mechanisms, specific chemicals used, life-cycle analysis, and other facts supporting the claim that this plant would save millions of tons of CO2 emissions per year. The man we initially found confessed that he could not answer these questions, but he redirected us to “the engineer,” who he assured us would have the answers. “The engineer” told us that the heat exchanger was a molten salt solution heated up to 560°C and stored at night in tanks made of a “special material” to prevent inefficient heat loss — facts we already knew from our chemistry coursework — but did not know what compounds this material was made of. Nor could he answer our questions regarding the initial CO2 investment to build the plant as well as to maintain it. Unfortunately, this experience was broadly indicative of any scientific conversations I tried to have (outside of the ACS cohort) at COP28. In the Blue Zone, I made it to 14 presentations on carbon capture, sequestration, use, and efficiency technologies. I heard lovely endorsements and statistics — “1769% efficiency boost,” “reduce energy consumption by up to 37%,” “we can achieve about 40% of climate goals through energy efficiency,” to name a few — but I did not meet a single scientist capable of explaining from where these magic numbers were coming. At one presentation on a new technology to help decarbonize concrete and the built environment, the presenter was a Yale architecture professor from the humanities department instead of the scientists who developed the technology. The professor’s presentation was captivating but completely unverifiable. I do not wish to make a claim that scientists were entirely absent from COP; amidst 110,000 people, even I find this highly unlikely. The point I do wish to make, however, is that they were terrifyingly scarce. Climate change is unique among the challenges facing humanity in that it is a fundamentally scientific issue, not an opinion-based one on which reasonable people can disagree. Yet scientists are not making the case for climate action — certainly not in the numbers that they should be. COP28 served as a forum for politicians and influencers to fight statistics with statistics, not make deductive, scientific arguments. This reduced the issue to one of rhetorical competence, not an honest give-and-take of reasons. This must change. Until then, I will ask again: Where were all the carbon scientists at COP? Steven LabalmePeople usually understand science and diplomacy perfectly when the two words are separated, not when they are combined. Science diplomacy is a term that generally refers to the intersection where the science component meets the diplomacy component. According to an article from the American Association on the Advancement of Science (AAAS), three categories under science diplomacy could be further defined: science in diplomacy, diplomacy for science, and science for diplomacy. Science in diplomacy refers to having the science components in the process of making international policies or diplomacy. Diplomacy for science means multilateral, cross-country collaborations on scientific projects, and science for diplomacy, on the other hand, talks about those international scientific projects that aim to foster better country relations. The three categories each play a role at the UNFCCC COPs.

The UNFCCC COPs, or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of Parties, is the most prestigious multilateral meeting that makes international climate policies. The most famous international climate policy produced by UNFCCC COPs so far is the Paris Agreement. After almost 30 years of the establishment of COPs, humankind finally decided to collectively act on climate change to limit the global temperature to below 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrial level. So how does science diplomacy play a role in UNFCCC COPs? Here I am listing down a few possible ways:

All three categories in science diplomacy serve different purposes and are equally important. The reason it is so important to have a science component in diplomacy is that many of the current issues we are facing today are transboundary and complex. But as a universal language, science is a strong tool to provide common ground for countries to initiate discussions. Of course, there are other social factors to consider when making policies, such as the Indigenous People's knowledge and social and environmental justice. Hopefully, we will be able to find a platform to integrate all these essential factors into the policy-making process and make all policymakers in the world believe in their importance. Author: Chia Chun Angela Liang https://www.linkedin.com/in/chia-chun-angela-liang/ |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed