|

By: Mohammed Aldulaimi

As we look at our world today, we are challenged with the climate change problem. For decades now, scientists have been finding more data proving the climate change. In fact, the Conference of the Parties (COP) is an initiative that helps address this particular problem. Every year and in a different city, political leaders and scientists meet to discuss plans against climate change. Yet, despite the many promising initiatives made during these meetings, decisive actions are yet to be made. Luckily, more people, including the general public, want change. Climate activism has been growing around the world, increasing the pressure on decision makers. Yet, there is another question that needs to be addressed: How can we make money out of this? You see, despite this sounding a bit greedy, it may be the answer we need. New inventions have always been driving changes in societies. Think about the industrial revolution, it transformed everything. With the introduction of new machines, various industries saw exponential growth. Additionally, new industries were also created, like the machine manufacturing industry. This growth brought new norms and habits in societies. For instance, the consumer culture we have now is a consequence of the revolution. In fact, this culture was influenced greatly by businesspeople. Upon seeing the potential, they began investing more into research and development (R&D). This allowed innovators to find jobs that let them do nothing but innovate. Countries and non-profit organizations were also investing into R&D in universities and research centers. More innovations were made, and more societies were changing. Businesses also started investing into marketing, driving more sales for their products. Brands were created, and cultures were made. Even today, we see many people that religiously follow certain brands. Businesses became very powerful, reaching more people and spreading their propaganda everywhere. Similarly, as more new startups prove that they can make profit out of eco-products, more investments will be available for them. More investments, means more innovation, which means more rapid change. Not only that, but the dominance of eco-brands, will also work to educate more people on climate change and sustainable lifestyles. This doesn’t only require innovation in products, but also in business models. Many countries have realized the importance of entrepreneurs in combating climate change. They have been promoting many “eco-preneurship” bootcamps and hackathons and providing more investments into this sector. In fact, this year’s COP had a special venue called the Startup Village. It featured many eco-startups with innovative ideas. There were companies recycling coffee waste, while others providing mobile software for monitoring farm produce. Hopefully, more companies will start incorporating sustainable practices into their business models. Therefore, rapid change may become more attainable for us.

0 Comments

Stevie Fawcett

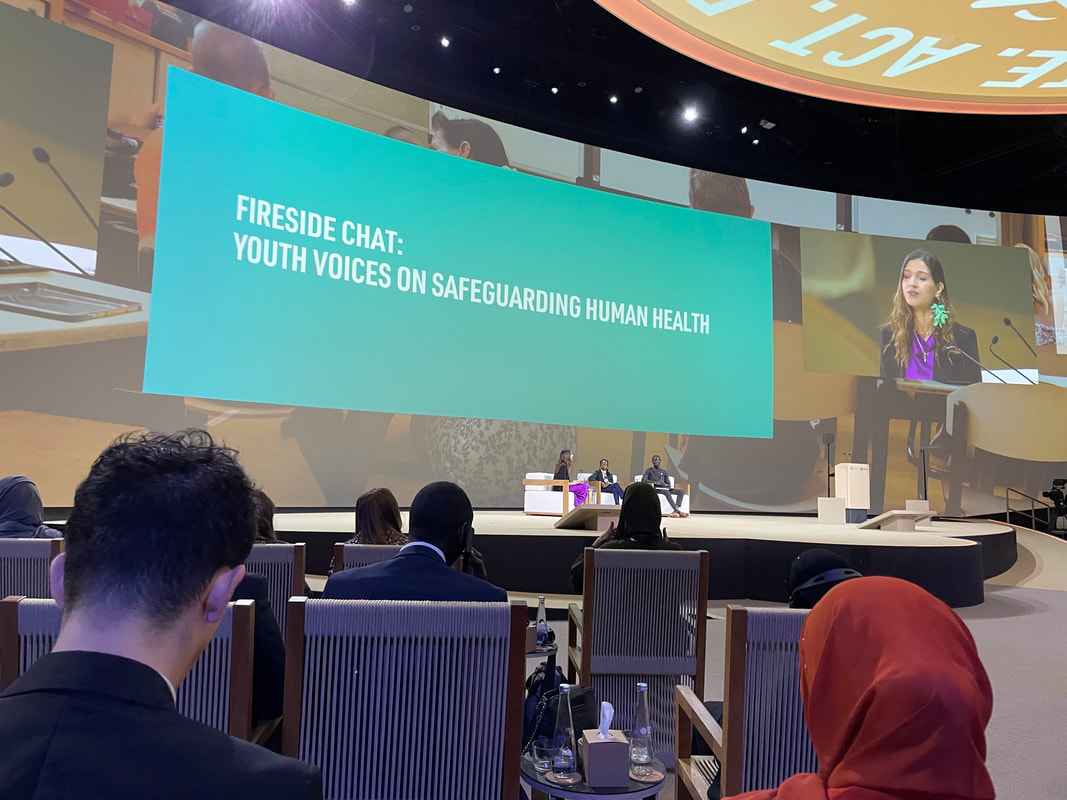

[email protected] For the first time ever, public health took center stage at a COP conference during COP28’s Health Day on December 3rd, 2023. Announcements made during Health Day included a one-billion-dollar commitment toward climate health, which seeks to prioritize health benefits of the people most affected by climate change. These funds are meant to support the Declaration of Climate and Health (1), which calls for action toward adaption and resilience related to climate health. This declaration, which has been signed by 148 countries, represents the most significant document from a COP conference that recognizes the importance of health in the context of climate change. This declaration outlines the integration of health into the climate strategies of each of the signing countries, including specific actions meant to be taken by each country. For the United States, the committed goals included decarbonization of the health sector and improving medical assistance to other countries in responding to health crises related to climate change. Beyond the discussions and announcements put forth during Health Day, COP28 also provided a platform for scientists and health workers to speak about how health is impacted by climate change in different parts of the world. These conversations went beyond the health issues I was personally aware of prior to my attending at COP28, and speak to the immensity of issues that stem from climate change. Below, I have highlighted some of the most significant topics that did not receive as much attention during Health Day. Mental Health: Many people, especially youth, commonly experience intense anxiety and stress in response to climate change. These stressors are also more likely to compound over time in underserved populations, as youth are more likely to experience traumatic events during development, such as forced relocation or the disruption of nature-based livelihoods. In indigenous populations, the destruction of nature caused by climate change can also destroy one’s sense of cultural identity. This has a huge impact on suicide rates and general mental health in indigenous communities. The mental health of climate leaders is also an important topic that is often neglected. These leaders experience an intense amount of stress and anxiety around their work, which can negatively impact productivity and happiness. Climate Change in Medical Schools: The production of fossil fuels not only alters the natural environment, but also increases risks of several diseases. Therefore, in the medical field, the production of fossil fuels is self-sabotage. This concept is central to climate health and has garnered significant support from students and staff at medical schools around the world. Many of the health leaders at COP28 are looking to incorporate climate health into the curriculum of medical schools, which in turn should teach the future doctors of the world important strategies to treating climate-related disease and decarbonizing medical practices. Educating the Public: The dangers of climate-related diseases are increasing, but not everybody knows this. Yet another facet to climate health is the ability to inform the public of the risks associated with climate change in the context of public health. Education also looks drastically different in different areas of the world. For instance, disease-carrying mosquitos are an important topic in the global south, while countries such as the United States may want to focus on the health impacts of natural disasters like wildfires and floods. 1 - https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/climate-change/cop28/cop28-uae-climate-and-health-declaration.pdf?sfvrsn=2c6eed5a_3&download=true By: Cailey Carpenter For two weeks in Dubai, there was a fiery energy that emanated from every square inch of the Convention Center. With each passing day, I could feel the pressure mounting on decision makers at COP28. But this sense of urgency wasn’t just contained to the decision makers. Tired of standing on the sidelines of countries’ frustrating acts of self-interest, youth and interest groups made their presence known at COP28. These activists didn’t shy away from protests despite the ‘shocking level of censorship’ of the UAE presidency. One protest in particular caught my eye: Not only did I find this activism a bold move in a country that produces 3.2 million barrels of petroleum products per day, I was taken by surprise when reading the sign entitled “NO CCS!”, CCS being shorthand for Carbon Capture and Storage. This was not an isolated event – messages against CCS ran rampant throughout COP28. Why would we oppose the our most promising method to remove carbon from our atmosphere? This is our hope at a net-negative carbon economy, and arguably, a key component of reaching net-zero carbon emissions in a reasonable time frame to combat the major effects of climate change. I understand the sentiment that CCS is a way by which big oil producers can avoid accountability for their actions by pushing the responsibility of emissions to CCS technologies/companies. It is true that avoiding a phase out of fossil fuels expecting a scale-up of CCS is an irresponsible and unsustainable solution. However, I don’t think this is a reason to completely discount CCS as a viable climate solution. CCS is often a controversial topic because many don’t understand the relative weight of the risks and benefits, so I found the blind rejection of CCS at COP28 troubling. This post aims to clarify the prospects of carbon capture and storage (CCS) for mitigating climate change.

The truth is: CCS technology is not as robust as we’d like it to be as a large-scale decarbonization solution. There are still major issues we need to deal with before implementing CCS worldwide – challenges that are scientific, engineering, and political in nature. In 2023, the IPCC estimated that even if CCS is deployed at current full capacity, it will only make up 2.4% of global climate mitigation strategy. Many of the promising CCS projects have either stalled or shut down. Selecting a location with the correct geochemical makeup for long-term storage is difficult. Monitoring CO2 capture and storage has its challenges because we can’t directly see a mile below ground where these plants often operate. But most of all, CCS is expensive with few direct benefits to the operator. CCS operations are estimated to cost $20-110 per metric ton of CO2 stored. The use of fossil fuels leads to emissions of 34 billion metric tons per year, so this adds up quickly. On top of this, what’s to gain from CCS beyond the common good? There is no financial incentive to set up and maintain a CCS project, and CCS comes with liabilities. Monitoring of CO2 remains a challenge, making leaks difficult to detect. If CO2 does leak out, the blame and disdain is directed towards the owners. Furthermore, there is ongoing debate among scientists as to whether pumping CO2 underground can increase seismic activity and trigger earthquakes, something world leaders aren’t willing to risk on behalf of disapproving populations. CCS cannot succeed without further innovation, and most importantly, regulation. Regulation on a global scale is a difficult endeavor, which is why COP is critical for achieving our climate targets. In my eyes, COP is a place where no climate solutions should be off-limits. COP shouldn’t end in empty promises; leaders must negotiate towards a plan of action that is feasible for all parties, even if this includes unconventional methods. Science and engineering innovation work quicker than negotiating policies, so the technical challenges should not be the limiting factor. We need to accelerate climate change mitigation more than ever, and CCS may play a key part in this. This leads us back to the statement that started this all: “NO CCS!”. While I agree with the message that CCS is not a means for fossil fuel producers to evade responsibilities for their significant contributions to the climate crisis, I believe this language can easily be interpreted in a way that perpetuates misinformation. The public can be easily influenced, so it is of vital importance for scientists and climate activists to be cognizant of the way they portray their arguments in order to avoid unintended (and possibly dangerous) side products of their good intentions. Where were all the carbon scientists at COP? Two and a half months ago, I headed to COP28 as a budding chemist, eager to explore the sustainable technologies being developed to fight the climate crisis. Day 1 got off to an auspicious start: In the Green Zone, my cohort and I quickly zeroed in on a group promoting Dubai’s planned implementation of a massive concentrated solar power plant by 2030. The sales pitch was wonderful, but as scientists, we were anxious to learn the underlying mechanisms, specific chemicals used, life-cycle analysis, and other facts supporting the claim that this plant would save millions of tons of CO2 emissions per year. The man we initially found confessed that he could not answer these questions, but he redirected us to “the engineer,” who he assured us would have the answers. “The engineer” told us that the heat exchanger was a molten salt solution heated up to 560°C and stored at night in tanks made of a “special material” to prevent inefficient heat loss — facts we already knew from our chemistry coursework — but did not know what compounds this material was made of. Nor could he answer our questions regarding the initial CO2 investment to build the plant as well as to maintain it. Unfortunately, this experience was broadly indicative of any scientific conversations I tried to have (outside of the ACS cohort) at COP28. In the Blue Zone, I made it to 14 presentations on carbon capture, sequestration, use, and efficiency technologies. I heard lovely endorsements and statistics — “1769% efficiency boost,” “reduce energy consumption by up to 37%,” “we can achieve about 40% of climate goals through energy efficiency,” to name a few — but I did not meet a single scientist capable of explaining from where these magic numbers were coming. At one presentation on a new technology to help decarbonize concrete and the built environment, the presenter was a Yale architecture professor from the humanities department instead of the scientists who developed the technology. The professor’s presentation was captivating but completely unverifiable. I do not wish to make a claim that scientists were entirely absent from COP; amidst 110,000 people, even I find this highly unlikely. The point I do wish to make, however, is that they were terrifyingly scarce. Climate change is unique among the challenges facing humanity in that it is a fundamentally scientific issue, not an opinion-based one on which reasonable people can disagree. Yet scientists are not making the case for climate action — certainly not in the numbers that they should be. COP28 served as a forum for politicians and influencers to fight statistics with statistics, not make deductive, scientific arguments. This reduced the issue to one of rhetorical competence, not an honest give-and-take of reasons. This must change. Until then, I will ask again: Where were all the carbon scientists at COP? Steven LabalmePeople usually understand science and diplomacy perfectly when the two words are separated, not when they are combined. Science diplomacy is a term that generally refers to the intersection where the science component meets the diplomacy component. According to an article from the American Association on the Advancement of Science (AAAS), three categories under science diplomacy could be further defined: science in diplomacy, diplomacy for science, and science for diplomacy. Science in diplomacy refers to having the science components in the process of making international policies or diplomacy. Diplomacy for science means multilateral, cross-country collaborations on scientific projects, and science for diplomacy, on the other hand, talks about those international scientific projects that aim to foster better country relations. The three categories each play a role at the UNFCCC COPs.

The UNFCCC COPs, or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of Parties, is the most prestigious multilateral meeting that makes international climate policies. The most famous international climate policy produced by UNFCCC COPs so far is the Paris Agreement. After almost 30 years of the establishment of COPs, humankind finally decided to collectively act on climate change to limit the global temperature to below 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrial level. So how does science diplomacy play a role in UNFCCC COPs? Here I am listing down a few possible ways:

All three categories in science diplomacy serve different purposes and are equally important. The reason it is so important to have a science component in diplomacy is that many of the current issues we are facing today are transboundary and complex. But as a universal language, science is a strong tool to provide common ground for countries to initiate discussions. Of course, there are other social factors to consider when making policies, such as the Indigenous People's knowledge and social and environmental justice. Hopefully, we will be able to find a platform to integrate all these essential factors into the policy-making process and make all policymakers in the world believe in their importance. Author: Chia Chun Angela Liang https://www.linkedin.com/in/chia-chun-angela-liang/ Stephen Fawcett [email protected] As climate change continues to alter the landscape or our planet, we are beginning to see large changes that affect our every-day lives. Massive wildfires have devastated large areas of the Americas, Australia, and Europe; sudden changes in precipitation and temperature have destroyed agricultural communities around the world; and melting glaciers and ice sheets have led to rising water levels that threaten coastal cities and islands. These are some of the most apparent effects of climate change, which have noticeable impacts on international economies, infrastructure, and wildlife. However, perhaps the most underappreciated aspect of these environmental repercussions is the impact they have on human health. With COP28 less than a week away, it is essential that public health be addressed in the context of climate change in order to strengthen public health systems and adapt to increasing incidences of human disease. Climate change and cancer In the United States, some of the largest signs of climate change have been the increasing number and intensity of wildfires that occur every year. Cities everywhere have experienced noticeable decreases in air quality, but the resulting smokey air may be more than an inconvenience. In fact, one study done at McGill University found that people who live closer to wildfires may have a higher risk of developing brain and lung cancer than those who do not (1). This would likely be due to the release of carcinogens and particulate matter from fires. This assumption also agrees with another study, which found that cancer deaths related to the presence of particulate matter have been increasing over the last 30 years (2). Researchers at the National Cancer Institute have been exploring the relationship between climate change and cancer as well, and have also noted that the hurricanes and storms that are strengthened by the effects of climate change may be wiping out the medical resources needed to treat cancer patients (3). Because of this, climate change may be increasing the incidence of cancer, as well as limiting our ability to treat it. Climate change and infectious disease Climate change has also had a significant influence on the movement and migration of animals and insects. As their ecosystems change, these organisms must relocate to survive, and when they do, they bring all sorts of pathogens with them. As a prime example, we can look at malaria. This disease is caused by a protozoan parasite which is transmitted by mosquitos. As climate change warms the planet, these pathogens can develop at faster rates (4). Additionally, there is also evidence that these warmer climates expand the habitable regions for mosquitos, and that climate-related disasters are creating more optimal conditions for mosquito reproduction (5). This aspect of climate change also affects viruses that are transmitted by mosquitos, and it isn’t the only example of how climate change creates a perfect storm for diseases to spread and persist. Topics at COP28 As an urgent issue related to climate change, public health will be an important topic at the upcoming COP28 climate conference in Dubai. In fact, this year will be the first time that a COP conference incorporates a “health day” into its programming (6). These sessions will cover everything from public health adaptation to health finance and will be an essential part of the climate discussion. Hopefully, they will take us one step closer toward building public health resilience in a time of uncertainty around the world. 1.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00067-5/fulltext 2. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935121013189 3. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2023/cancer-climate-change-impact 4. http://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/climate-change-and-malaria-complex-relationship#:~:text=At%20lower%20altitudes%20where%20malaria,on%20the%20burden%20of%20disease. 5. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01569-6/fulltext#%20 6. https://www.cop28.com/en/health-events/ Author: Benjamin Shindel, PhD Candidate in MSE at Northwestern University

Contact: [email protected] While the proceedings at the UN Climate Change Conference will undoubtedly focus on avoiding the global catastrophic risks that climate change threatens, another topic will compete for attention in 2023. Over the last few years, the risks associated with the development of artificial intelligence have risen to the forefront, reaching a fever pitch with the release of software from tech industry leaders that suggests humanity is on the cusp of developing “weakly general artificial intelligence”, or an AI that can rival the average human in its capabilities. OpenAI, Google, Meta, and others have developed AI capable of writing, locomotion, logical reasoning, and the interpretation of visual and auditory stimuli. Simultaneously, researchers around the world have made substantial progress in the application of narrow AI tools for specific scientific problems. While AI offers tremendous promise in accelerating humanity’s timelines for solving grand challenges, including climate change, it also poses an existential risk to humanity. While there’s an ongoing debate as to the shape, likelihood, and severity of this risk, many of the world’s top AI scientists and thinkers have signed onto statements endorsing the need for action to study and avoid the risk of extinction from a superintelligent AI. The recent leadership crisis/coup at OpenAI, the current unquestionable vanguard of AI development serves as a particularly shocking example of the rift within the AI world between pushing forward AI capabilities and ensuring the safety of humanity. This specific existential risk is challenging to describe in a short blog post, and it is even more challenging to convince the reader of its seriousness, since it can sound like science fiction, but I’ll try here:

While the effects of anthropogenic climate change are massive and have already begun, it is unlikely that they pose a true existential risk to the survival of humanity. It can be challenging to balance attention between a ~100% proposition of damaged ecosystems, enormous infrastructure costs, and issues of food insecurity, climate refugee crises, etc, that will develop over decades… against a ??% proposition of a world-destroying machine intelligence. There are parallels to be made to the rise of nuclear technology, where atomic fission posed a potentially unlimited clean energy source alongside the growing threat of mutually assured destruction pursued by the parties of the cold war. At COP28, I expect that people will focus on the more pleasant or pedantic aspects of artificial intelligence. There will be discussions of the benefits of AI for scientific research in the fields of inquiry that can benefit climate and clean energy technology. AI has already proven invaluable in searching for more efficient materials for energy generation and storage, finding catalysts to synthesize clean fuels, and even in the genetic engineering of more resilient crops. There will also be discussions on the risks of AI in spreading misinformation about the climate, or perhaps for its benefits in combating that misinformation. Unfortunately, these discussions will likely miss the crux of the debate. The growing power of AI will be immense and if we’re lucky, we’re just beginning to scratch the surface of some of the utopian benefits that it can provide for the world. It’s easy to imagine a world where the efficiency, automation, and optimization brought on by tools that augment our species’ intelligence can lead to rapid solutions for the major climate challenges of today. However, if we’re unlucky, the risks of AI could outweigh these benefits, perhaps dramatically so. Key Issues to Watch at COP28 from an Early Career Scientist’s Point of View: An One-page Summary20/11/2023 Date: 11/20/2023

Author: Chia Chun Angela Liang Contact: [email protected] Affiliation: PhD candidate at UC Irvine, USA; Science and Technology Advisor at Open Dialogues International Foundation; Western Onboarding Chair, National Science Policy Network With COP28 coming in 2 weeks, more information has been released from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) authority. As an early-career scientist representing the American Chemical Society and the Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organizations (RINGO) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), it is fascinating to attend COP28 compared to other COPs. First of all, the COP28 leadership may present a conflict of interest to the UNFCCC itself. The president-designate of COP28, Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, runs the country's largest oil company, i.e., the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. With its plan to expand fossil fuels, it presents a conflict of interest with the main goal of the UNFCCC as stated in Article 2 Objective, which requires parties to stabilize greenhouse gas emissions to a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic disturbances to the climate system [ref 1]. As a scientist who understands the physical impacts of fossil fuels on our climate system [ref 2], one key point to watch this year at COP28 is how the COP presidency discusses the role of fossil fuels in the future. In addition to this, there are other key topics that are worth taking a look at as scientists:

As an early-career scientist, COPs might be overwhelming because there are many items and topics being discussed and negotiated at the same time. Besides, there are hundreds of side events, exhibitions, and possibly protests happening in both the Blue Zone and the Green Zone every day. There are many ways that an early-career scientist can make an impact, and hopefully this article will be helpful to those early-career researchers who are attending COP28 this year in Dubai, UAE. Reference

By David Baldwin

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change calls for the stabilization of atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) to a level prevents further human interference with the climate. To meet this goal, it requires carbon sequestration: the capture and storage carbon back to either the environment or engineered system. That is where wetlands come in. It is essential to appreciate the carbon sequestration capabilities of wetlands, even in urban settings. These ecosystems, whether in natural or constructed forms, possess a remarkable ability to lock away atmospheric carbon. Through photosynthesis, the wetland plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and convert it through a series of molecular processes into cellulose and other carbon compounds in plants, effectively removing excess carbon from the atmosphere. Moreover, wetlands, by their waterlogged nature, inhibit the decomposition, of organic matter, allowing the carbon of the organic matter to accumulate in the form of peat-rich soils. This carbon storage is, in essence, an effective mitigation strategy against climate change. It's akin to a vault or carbon, securely tucked away from the atmosphere for centuries. The protection of wetlands holds significant implications for Earth's natural carbon cycles, as a substantial proportion of the planet's carbon resides within wetland soils. For example, peatlands in tropical regions house an impressive carbon pool exceeding 600 petagrams (PgC), or billion metric tons, making them some of the world's largest carbon reserves. This is comparable to the carbon stored in global forest biomass. In the continental U.S., wetlands a reservoir amounting to 13.5 billion PgC according to the Global Change Research Program Carbon comes in many forms, and it is not just the abundant carbon dioxide that wetlands can sequester. Methane is a hydrogen and carbon compound about 25 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. Wetlands, however, have a fascinating dual role concerning methane. While they can be sources of methane due to anaerobic (low oxygen) conditions in waterlogged soils, they are also sinks: a natural mechanism for nutrient storage. Microorganisms within wetlands, in a remarkable act of ecological balance, consume much of the methane they produce, preventing its release into the atmosphere. This helps in keeping a check on methane levels and mitigating its impact on global warming. I now want to turn to what we can do with all this information. Wetlands are a recurring topic of discussion at COP events. During COP 28, a significant focal point in the discourse on water quality and access is the enhancement of urban water resilience. I eagerly anticipate engaging in productive conversations regarding the contribution of wetlands to this critical issue. Urban wetlands are clear player in reaching the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 13: Climate Action. I believe they are also a powerhouse in environmental justice and can aid in our journey toward reducing inequality and sustainable communities: Goals 10 and 11. These ecosystems, natural or engineered, offer a beacon of hope, especially for marginalized communities facing disproportionate environmental challenges. Minoritized groups often find themselves residing in areas more vulnerable to flooding and lacking the necessary resources for recovery. Wetlands play a pivotal role in maintaining water quality, both within their boundaries and downstream. Their unique hydrological and biological characteristics (the soil, plants, and flow of water) allow them to absorb excess nutrients and filter out various contaminants. This purification capacity ensures that water, as it flows through wetlands, emerges cleaner and less burdened by harmful substances. In this manner, wetlands play a fundamental role in mitigating the detrimental impacts of chemical pollution, thus preserving the health of aquatic ecosystems, and safeguarding the surrounding communities. In a similar process, a process called sedimentation relies on the slow-moving nature of water, allowing nutrient-rich particulate matter sediments to settle. As water flows through the wetland, these sediments are captured and retained, preventing their downstream transport. Additionally, aquatic plants within wetlands serve as biological sponges, absorbing nutrients from the water. Through a process known as nutrient assimilation, these plants incorporate nitrogen and phosphorus into their tissues, effectively removing excess nutrients from the ecosystem. A healthy wetland has nutrient rich sediment, and nutrient poor water, and a healthy environment promotes a healthy community. Protecting wetlands is not just a matter of ecological importance; it's a matter of justice and equity in our pursuit of sustainability.  By Mohammed Aldulaimi The year 2050. People have stopped recycling their waste since 2024. Factories are throwing their waste into the ocean. Governments succumbed to economic pressures, and they’ve abandoned the international environmental agreements they once had. Plastics are still being used, now more predominantly, and are not being recycled. Fossil fuel is still our only major source of energy, continuing to pump greenhouse gases into our atmosphere. Despite the early concerns about global warming, no action has been taken to reverse the effects, and now, the temperatures around the globe are 6˚ F higher than they were in the past century. With some countries having reached as high temperatures as 115 degrees in 2018, many of these countries are on the verge of turning to real-life furnaces and may eventually become ghost towns. IOP Publishing Where some cities and villages are experiencing deadly droughts and famines, other cities are on their way to being completely flooded and submerged under the ocean, succumbing to the drastic sea level rise, another product of global warming. On the other hand, animals are quickly becoming extinct. As we continue to cut down forests and fuel global warming, many animals are losing their habitats and experiencing deadly temperatures. For instance, red wolves, Bornean orangutans, and Hawksbill turtles have vanished and haven’t been observed since 2030, they’ve gone extinct. We’re slowly losing our planet, not in a thousand or million years, but it’s happening now, in real-time. Public health has seen better days. Many, once known as, healthy adults, are now frequent patients in hospitals. Our diet has been enormously affected by the drastic environmental change we ceased to address. Now, it is very hard to find food that is clean of plastic particles. The microplastic ‘epidemic’, being untreated for years, has become part of our daily diet. Plastics are known to cause damage to our cells, slowly degrading our overall health and our life expectancy. Today, wildfires have become very frequent and have been worsening our air quality and destroying our forests. Air pollution is a global health hazard that seems to have become an intrinsic character of our cities. For instance, cities like New Delhi have become so extremely polluted, they are now unsafe environments for many people. Air pollution, partially caused by wildfires, may potentially contribute to cancer occurrence in global populations. The age expectancy around the world is quickly shrinking, and so is the life quality of people. Whether it’s because of our food or our environment, the Earth is on its way to becoming another ghost planet in the universe, vacant of the once-thriving creatures that walked on it. Global environmental conditions seem to only worsen. It is not only a simple rise in temperatures, but a global loss of the quality of life. Is it enough of a wake-up call for us? Our world is no longer our envisioned utopia, did we really give up? Is there still hope for change? In reality, it’s never too late. Now, government entities have realized their mistake. Cooperations are joining hands again, in an attempt to reverse the impact we humans are contributing to. In fact, you can become part of the change. It’s now only one click away (and possibly a few thousand miles away). |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed