|

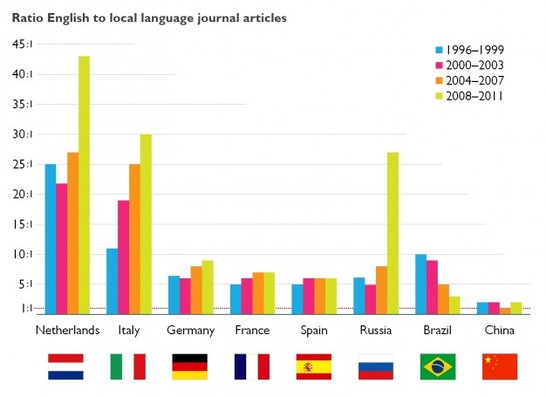

In the process of applying to be an ACS delegate at COP22, I found myself on the official COP22 YouTube channel looking to learn as much as possible about UN Climate Change Conference proceedings before completing my application. Back in June, I clicked on this one, only to realize I was unable to understand a single word. This speech by Her Royal Highness Princess Lala Hasnaa of the Kingdom of Morocco is, of course, in Arabic, the official language of Morocco. While I had a moment of frustration that there were no English subtitles, I also understood that it was silly for me to assume a speech for an international conference would be in English. Language diversity should certainly be both expected and valued in international relations. While not necessarily apparent to those engaged with UN proceedings via English-speaking media outlets, social media and other digital communications display the multilingualism of UN proceedings. Since June, the COP22 steering committee launched their official communications campaign starting August 1st. This campaign included a short video titled “Just open your eyes,” which highlights the natural resources of Morocco and the importance of sustaining them. This video is available in classical and dialectal Arabic, dialects of Berber, French, English and Spanish.  COP22 Facebook cover graphic COP22 Facebook cover graphic Language diversity is notable at COP22, the first COP to communicate in four of the UN’s six official languages. Official materials are communicated in Arabic, French, English and Spanish. While multilingual communication is evident in official conference branding and materials on their website, posts to their Facebook and Twitter accounts are primarily in Arabic and French (ce que je peux lire, heureusement). Arabic is the official language of Morocco along with Tamazight, a Berber language. In addition, French is often the language of business and diplomacy due to colonial influences in Northwest Africa. Equitable language representation is important in international diplomacy. Mutual understanding is absolutely essential when concerning agreements between nations, especially when the number of nations represented is nearly 100… which is the case at COP 22. Furthermore, the more languages in which UN proceedings are available, the more everyday people can, at least in theory, have access to this information. However, the logistics of communicating in more than one language can make things complicated, translation is never perfect and there is usually some trade off between language diversity and mutual comprehensibility. Of particular interest to me at COP 22 is the importance not only of multilingual communication, but multilingual communication of science. While studying in Windhoek, Namibia my junior year of college, I became interested in the dynamics of language in science education. While the official language of Namibia is English (as in many African countries since the colonial era), most of the university students and professors I interacted with spoke it as a second, third, or even seventh language. During a lab session I overheard a debate between several students regarding whether introductory science courses should be taught in English, to prepare students for the heavy focus on English in higher science education or in native languages, so students would have stronger understanding of the concepts. Since English is the language of professional science to such a high degree, it is clear why schools may choose to emphasize English in their science courses. But what does this mean for nonnative speakers? What does this mean for science and its place in the world? A similar debate exists for international negotiations. Is it better to choose one language for all negotiations, maybe a neutral language such as Esperanto (created in 1887 as a neutral, combination of European languages), or to communicate in all languages? How does language diversity affect the efficacy of international policy and debate? This COP is already reputed to be the COP of action, where global leaders move from lofty ideals and vague goals to concrete plans. While the Paris Agreement received much media fanfare, Morocco must be the time when actions begin to come into place including funding and further logistics. The support of actions to combat a changing global climate will require communication and outreach in many global languages. As we approach COP22, I am particularly interested by how language diversity is both encouraged and limited in international debate. How does language diversity affect international relations? How does the dominance of English in science affect global science literacy and how does science literacy affect the course of international policy? Sources:

Speech from SAR Lala Hassna: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXvCcQSw0Sg Language Priviledge: https://linguisticpulse.com/2013/06/26/language-privilege-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters/ COP22 Launches Communications campaign: http://www.cop22.ma/en/cop22-launches-communications-campaign-raise-awareness-climate-change COP Digital Communications: http://www.cop22.ma/en/cop22-digital-communications UN Official Languages: http://www.un.org/en/sections/about-un/official-languages/ English in Science: https://www.researchtrends.com/issue-31-november-2012/the-language-of-future-scientific-communication/ COP22 and action: http://cop22.ma/en/cop22-roadmap-devoted-action

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed