|

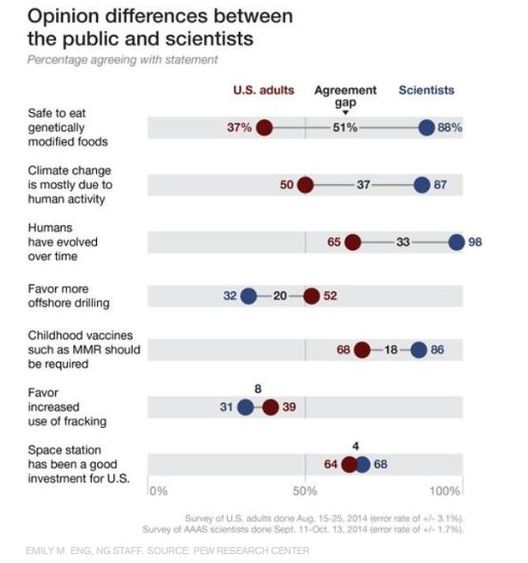

Scientists and the public don’t always see things in the same way. In fact, a recent Pew Research Center study identified a significant “agreement gap” for several controversial issues including climate change. While 87% of scientists agreed that climate change is primarily due to human activity, 50% of US adults held the same opinion, an agreement gap of 37%. From GMOs and vaccinations to evolution and climate change, controversy and skepticism towards scientific information seem to be everywhere these days. Regarding climate change, this controversy has dangerous potential. The more politicians perceive (accurately or otherwise) that climate change is not a priority for their constituencies, the less likely they will be to support initiatives to decrease carbon emissions, increase investment in renewable energy, and support other measures to combat a changing climate.  So what do we do to close this gap? Improve scientific literacy! Many may argue that if people have a better understanding of the issues at hand, they would agree with the majority of scientists. However, upon scrutiny, this assertion is oversimplified at best and potentially problematic. Simply throwing more scientific information at the public might not be the best answer for closing the agreement gap between scientists and the public. In fact, work from the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale Law School found that higher levels of science literacy and quantitative reasoning actually increase cultural polarization on issues such as climate change. Work from Dan Kahan and the Cultural Cognition Project identifies identity-protective thinking as the primary problem with science communication, why scientists have so much trouble making their ideas and research heard and understood in the public sphere. While one might assume that the public simply doesn’t know enough about science to understand or interpret scientific risk information, Kahan’s work suggests otherwise. According to identity-protective cognition, “People who are motivated to form perceptions that fit their cultural identities can be expected to use their greater knowledge and technical reasoning facility to help accomplish that—even if it generates erroneous beliefs about societal risks.” Thus, while I certainly do not wish to argue against improving science literacy since that is my primary goal in attending COP 22 as an ACS representative this fall and sharing reflections with my university community, I do agree with Kahan that it is not by any means the cure-all to climate controversy. Scientists need to find ways to communicate without attacking people’s strong held identities and as Kahan would argue… we need more science on science communication to help us figure out how to do just that.

Science literacy is about increasing the scientific knowledge people have access to, but science communication is about how that information is transferred. According to Kahan, people tend to use scientific information not to challenge their thinking, but to support beliefs that have already been shaped by their worldview. As a National Geographic feature article explains, “Science appeals to our rational brain, but our beliefs are motivated largely by emotion, and the biggest motivation is remaining tight with our peers […] We believe in scientific ideas not because we have truly evaluated all the evidence but because we feel an affinity for the scientific community.” So the real question becomes not how can we more effectively spread scientific information, but how can we more effectively cultivate public affinity for science and scientists. How can we cultivate recognition of common humanity capable of mutual understanding despite conflicting worldviews between scientists, non-scientists and everyone in between? Sources: Opinion gap graphic: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/06/150129-public-opinion-aaas-health-education-science/ A nice summary blog post of 2010 cultural cognition research from Kahan: http://www.culturalcognition.net/blog/2012/10/29/the-science-communication-problem-one-good-explanation-four.html 2013 paper from Dan M. Kahan: http://www.culturalcognition.net/browse-papers/making-climate-science-communication-evidence-basedall-the-w.html National Geographic feature: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2015/03/science-doubters/achenbach-text

1 Comment

Reiko Callner

16/10/2016 02:52:26 pm

Terrific article! But what a cliffhanger. How are we going to do that?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed