|

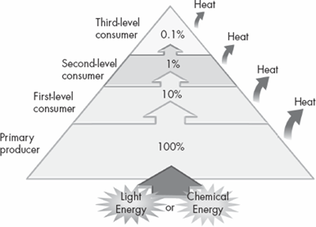

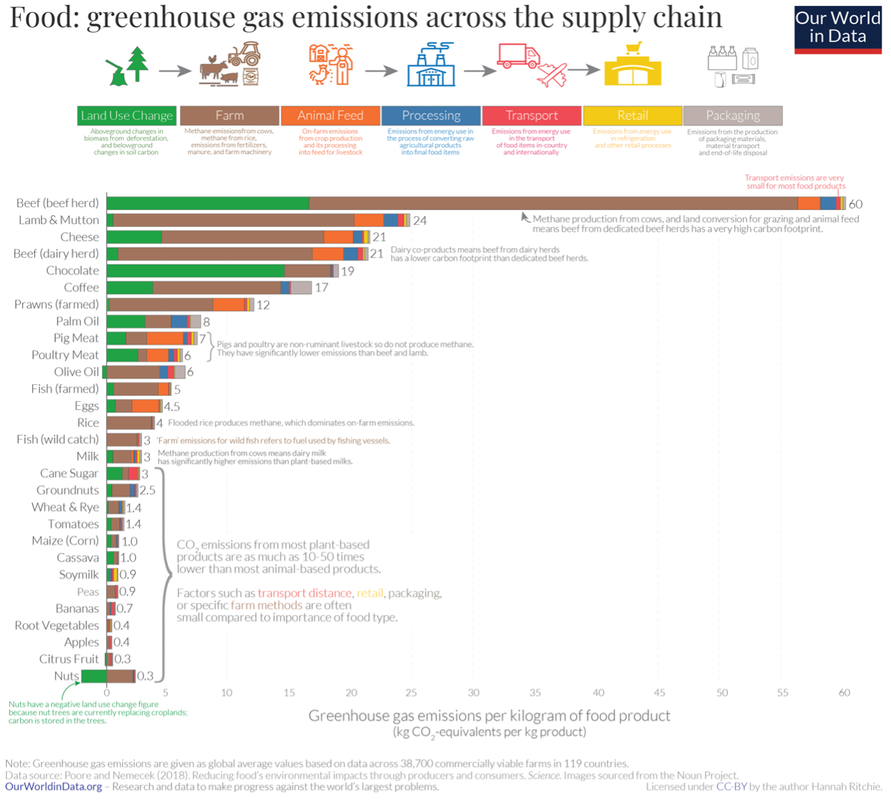

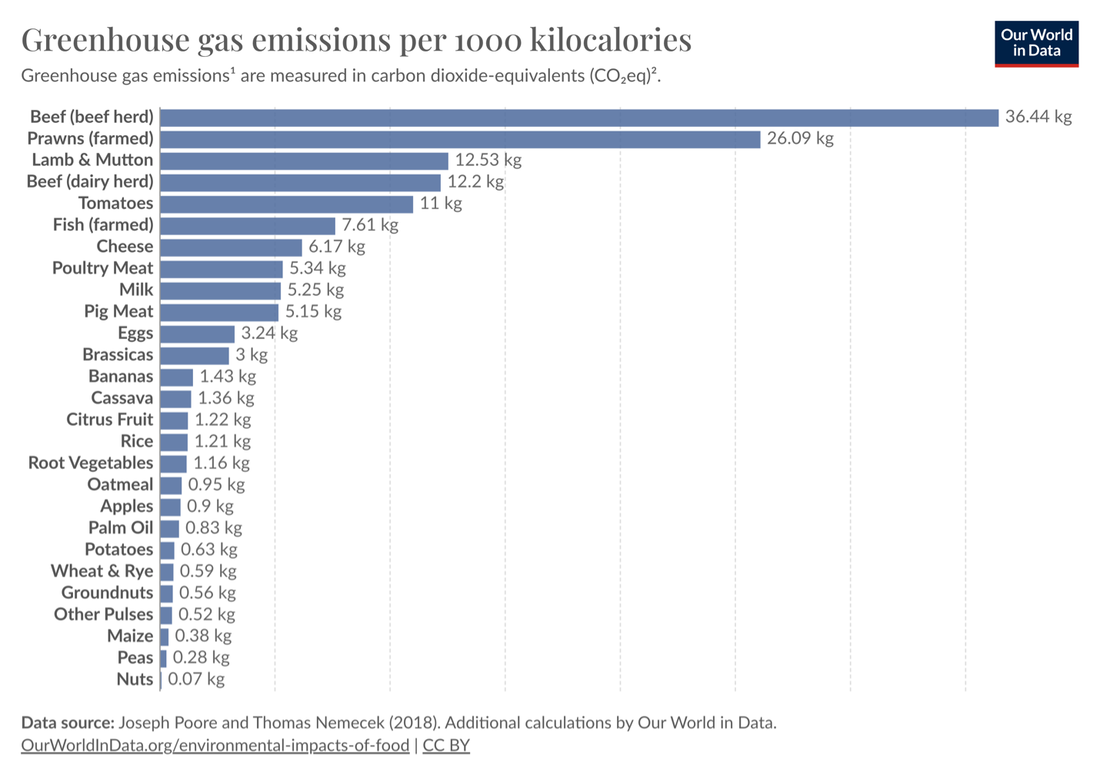

By Cailey Carpenter Eat plant-based! Buy local produce! These may be claims you’ve heard in connection to reducing your environmental impact. You may be wondering: Are these claims founded? How much do your food habits affect your carbon footprint? Globalization has disconnected citizens in developed countries from the source of their daily meals, making it difficult to see the direct impacts our food choices have on the environment. Where do our food emissions come from? Food accounts for approximately 26% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced by humans. In the United States, food is responsible for 10-30% of the average household carbon footprint; this category is the third largest, preceded only by transportation and housing. These numbers may not seem particularly shocking, as we all rely on food to survive day-to-day. It is easy, and reasonable, to focus efforts on reducing less necessary emissions, such as biking instead of walking or making sure to turn the lights off when leaving a room. However, many people don’t realize that their choices in the grocery store dictate whether they are releasing 5 or 15 tons of CO2 equivalents (CO2e) into the atmosphere annually. Consider this: one ton of CO2 requires an offset of approximately 50 trees to offset. This means that small lifestyle changes to reduce the GHG emissions of your diet can make the same environmental impact as planting 500 trees. These numbers can be broken down further into categories such as land use, farming practices, resources, processing, and transport. In 2018, Poore and Nemecek published a comprehensive study of the environmental impacts of farms in 119 countries that make up 90% of global food consumption. The results of this study are well summed up by this figure from Our World In Data: Our World In Data What’s the deal with plant based? It can be seen from the graph that there’s a large disparity in the total greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram between produce such as peas or wheat and red meats such as beef or lamb. We may rationalize this by considering that 1 kg of beef offers 2,500 Calories, while 1 kg of peas only offers 814 Calories of energy to the body. When normalizing these CO2 emissions to dietary Calories offered, though, we see a strikingly similar result:  Trophic Pyramid Trophic Pyramid Our World In Data Animal-based consumption results in significantly higher CO2 emissions, despite the higher caloric value per unit mass of these products. In the average American diet, approximately 75% of the GHG emissions from food are a result of meat and dairy. However, there’s no need to splurge on expensive plant-based imitation meats to reduce your carbon emissions. Legumes (tofu, groundnuts, other pulses – chickpeas, lentils, peas) are a significant alternative source of protein that results in only a fraction of the carbon footprint of meats and their derivatives (and a fraction of the cost!). In fact, research shows that a vegetarian diet saves an average of $2 per day compared to the traditional American diet. Why do animal products result in much higher emissions? I find this easiest to think of in terms of the trophic pyramid. Plants are primary producers, meaning that all of their energy comes from the sun. Furthermore, the biomass of these photosynthetic plants is made up entirely of CO2 from the atmosphere that has been converted to sugars, lignin, and cellulose. The species that eat these producers must take these compounds and transform them into smaller compounds that are digestible in their metabolism. This process takes energy, and only approximately 10% of the energy (calories) from this plant are transferred to the consumer. 10% is lost as heat at each level, meaning herbivores conserve 10% of the energy from the food they eat, while carnivores gain only 0.1-1% of the initial energy from their food. Metabolism works by expelling CO2, and moving up trophic levels requires more metabolic cycles to occur to get the energy we need. Eating plant-based can result in a ten-fold decrease in CO2 production in metabolism alone. Furthermore, cattle produce large amounts of methane (CH4), which has over 80 times the Global Warming Potential (GWP) as CO2. Buying local and in-season A first step for many people in their journey of sustainable eating begins by frequent trips to the farmers market to buy local produce. This effort supports lower environmental costs from transport of goods, but often comes with a higher price tag. Are these efforts worth it? It depends on a few factors.

Food waste Food waste accounts for 25% of food emissions, equating to 6% of total GHG emissions. In the United States alone, 119 billion pounds of food enters landfills – this is 30-40% of all food in the country. Some of this waste is a result of food loss in transport, but a majority of food waste comes from individuals and restaurants. Food waste makes up 24% of landfills, where it rots to produce methane, and 22% of combusted waste, where it enters the atmosphere directly as CO2, CO, and particulate matter (PM) that contribute to global warming. While food is a necessary commodity, food waste is not. Actions such as planning meals and engaging in food waste recovery (e.g. donation to food banks) can have a significant impact on your carbon footprint while contributing to other UN Sustainable Development Goals. Where do we go from here?

COP28 marks the halfway point between the 2015 Paris Agreement and the 2030 goals to limit GHG emissions to 50% of their 2005 levels. While food systems will not be the most pressing topic at this COP, this conversation is crucial for multi-level climate action. While ordinary citizens may not have a large impact on the politics of oil reserves or land use, they can directly impact climate change by making environmentally conscious decisions when it comes to their meals.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed