|

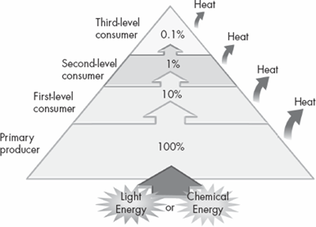

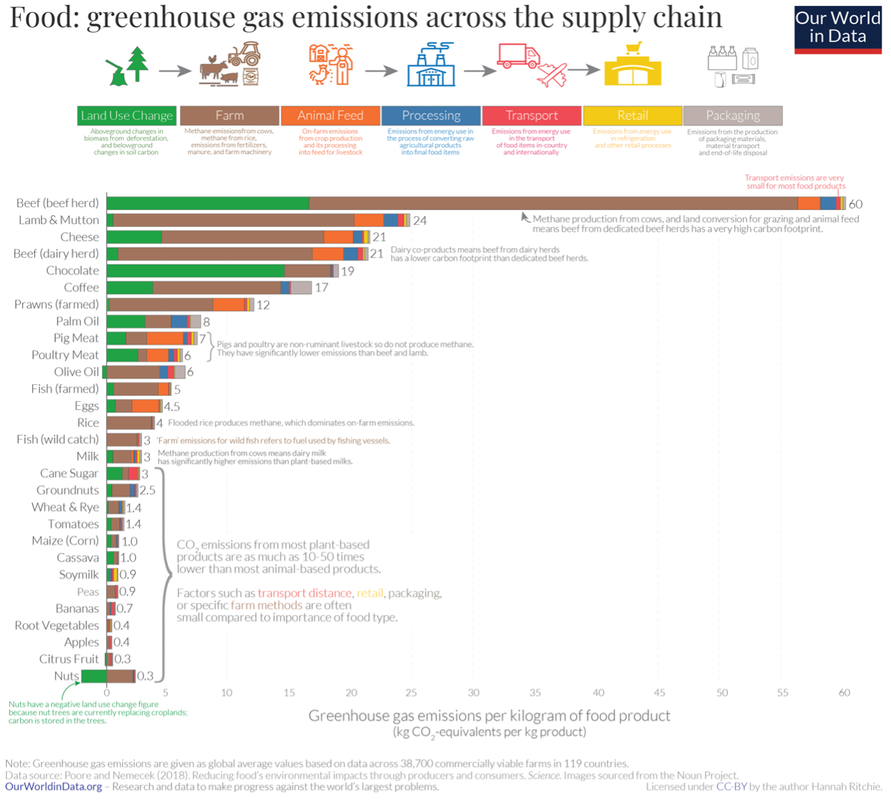

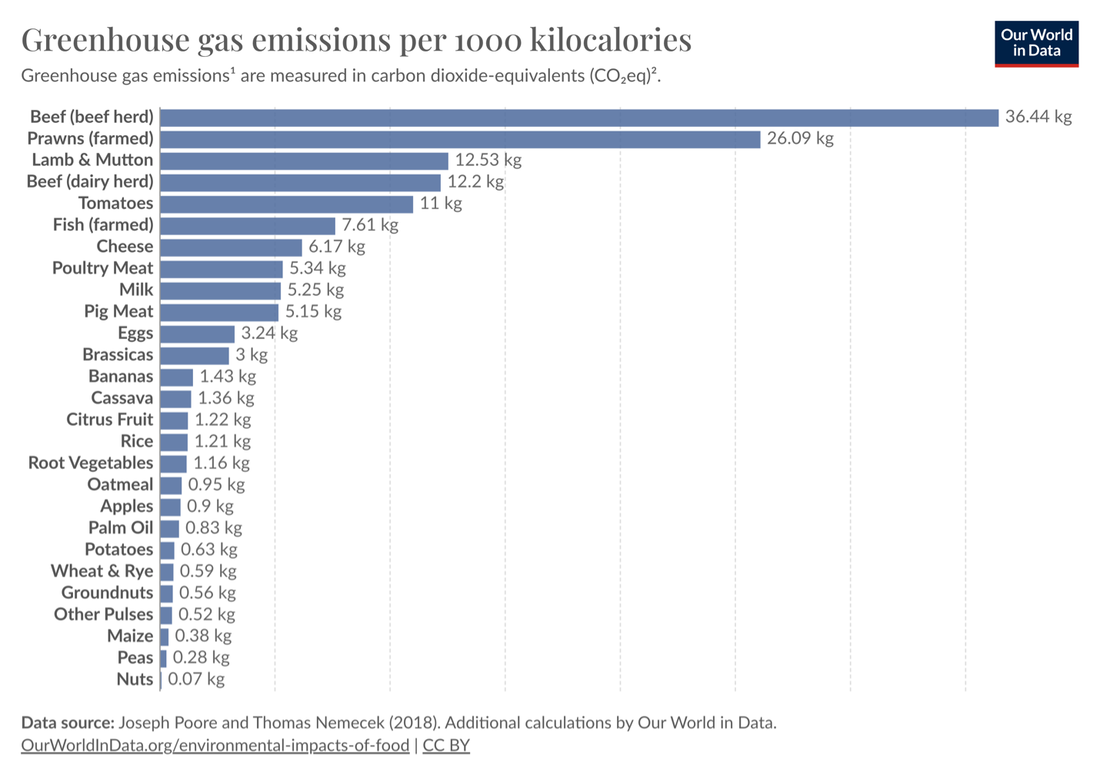

By Cailey Carpenter Eat plant-based! Buy local produce! These may be claims you’ve heard in connection to reducing your environmental impact. You may be wondering: Are these claims founded? How much do your food habits affect your carbon footprint? Globalization has disconnected citizens in developed countries from the source of their daily meals, making it difficult to see the direct impacts our food choices have on the environment. Where do our food emissions come from? Food accounts for approximately 26% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced by humans. In the United States, food is responsible for 10-30% of the average household carbon footprint; this category is the third largest, preceded only by transportation and housing. These numbers may not seem particularly shocking, as we all rely on food to survive day-to-day. It is easy, and reasonable, to focus efforts on reducing less necessary emissions, such as biking instead of walking or making sure to turn the lights off when leaving a room. However, many people don’t realize that their choices in the grocery store dictate whether they are releasing 5 or 15 tons of CO2 equivalents (CO2e) into the atmosphere annually. Consider this: one ton of CO2 requires an offset of approximately 50 trees to offset. This means that small lifestyle changes to reduce the GHG emissions of your diet can make the same environmental impact as planting 500 trees. These numbers can be broken down further into categories such as land use, farming practices, resources, processing, and transport. In 2018, Poore and Nemecek published a comprehensive study of the environmental impacts of farms in 119 countries that make up 90% of global food consumption. The results of this study are well summed up by this figure from Our World In Data: Our World In Data What’s the deal with plant based? It can be seen from the graph that there’s a large disparity in the total greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram between produce such as peas or wheat and red meats such as beef or lamb. We may rationalize this by considering that 1 kg of beef offers 2,500 Calories, while 1 kg of peas only offers 814 Calories of energy to the body. When normalizing these CO2 emissions to dietary Calories offered, though, we see a strikingly similar result:  Trophic Pyramid Trophic Pyramid Our World In Data Animal-based consumption results in significantly higher CO2 emissions, despite the higher caloric value per unit mass of these products. In the average American diet, approximately 75% of the GHG emissions from food are a result of meat and dairy. However, there’s no need to splurge on expensive plant-based imitation meats to reduce your carbon emissions. Legumes (tofu, groundnuts, other pulses – chickpeas, lentils, peas) are a significant alternative source of protein that results in only a fraction of the carbon footprint of meats and their derivatives (and a fraction of the cost!). In fact, research shows that a vegetarian diet saves an average of $2 per day compared to the traditional American diet. Why do animal products result in much higher emissions? I find this easiest to think of in terms of the trophic pyramid. Plants are primary producers, meaning that all of their energy comes from the sun. Furthermore, the biomass of these photosynthetic plants is made up entirely of CO2 from the atmosphere that has been converted to sugars, lignin, and cellulose. The species that eat these producers must take these compounds and transform them into smaller compounds that are digestible in their metabolism. This process takes energy, and only approximately 10% of the energy (calories) from this plant are transferred to the consumer. 10% is lost as heat at each level, meaning herbivores conserve 10% of the energy from the food they eat, while carnivores gain only 0.1-1% of the initial energy from their food. Metabolism works by expelling CO2, and moving up trophic levels requires more metabolic cycles to occur to get the energy we need. Eating plant-based can result in a ten-fold decrease in CO2 production in metabolism alone. Furthermore, cattle produce large amounts of methane (CH4), which has over 80 times the Global Warming Potential (GWP) as CO2. Buying local and in-season A first step for many people in their journey of sustainable eating begins by frequent trips to the farmers market to buy local produce. This effort supports lower environmental costs from transport of goods, but often comes with a higher price tag. Are these efforts worth it? It depends on a few factors.

Food waste Food waste accounts for 25% of food emissions, equating to 6% of total GHG emissions. In the United States alone, 119 billion pounds of food enters landfills – this is 30-40% of all food in the country. Some of this waste is a result of food loss in transport, but a majority of food waste comes from individuals and restaurants. Food waste makes up 24% of landfills, where it rots to produce methane, and 22% of combusted waste, where it enters the atmosphere directly as CO2, CO, and particulate matter (PM) that contribute to global warming. While food is a necessary commodity, food waste is not. Actions such as planning meals and engaging in food waste recovery (e.g. donation to food banks) can have a significant impact on your carbon footprint while contributing to other UN Sustainable Development Goals. Where do we go from here?

COP28 marks the halfway point between the 2015 Paris Agreement and the 2030 goals to limit GHG emissions to 50% of their 2005 levels. While food systems will not be the most pressing topic at this COP, this conversation is crucial for multi-level climate action. While ordinary citizens may not have a large impact on the politics of oil reserves or land use, they can directly impact climate change by making environmentally conscious decisions when it comes to their meals.

0 Comments

By: Tehreem Hussain

Climate change and antimicrobial resistance are intrinsically intertwined; this is one of the primary ways that rising temperatures are disrupting human health systems across the globe. The two main ways through which climate change exacerbates antimicrobial resistance are by creating greater areas of overlap between zoonotic species and humans, along with the increased use of antibiotics caused by the COVID-19 pandemic resulting in larger amounts of contaminants saturating natural water bodies. Even without the realities of climate change, antimicrobial resistance is a large public health concern; in the European Union alone, 670,000 infections have been reported annually and these infections have resulted in 33,000 deaths. However, with the environmental impact of climate change intersecting with global human health systems, the problem becomes much more dire. In 2023, the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) published a report outlining how climate change is linked to the transmission and proliferation of antimicrobial resistance. The report also highlighted the fact that pharmaceutical manufacturing, food production systems, and the healthcare delivery industry all contribute heavily to the rise of antimicrobial resistance. Like other climate change related issues, antimicrobial resistance does not target communities and countries uniformly. According to a study published in The Lancet in 2022, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) had 1.5 times higher fatality rate in relation to antimicrobial resistance in relation to their high-income country counterparts. Given that the United States Agency for International Development estimated that the effects of climate change will disproportionately impact human health in LMICs, it can be reasonably deduced that this trend will translate to antimicrobial resistance rates as well. Dr. Scott Roberts, an infectious diseases specialist at the Yale School of Medicine told CNN in a statement following the publishing of the UNEP report that, “Climate change, pollution, changes in our weather patterns, more rainfall, more closely packed, dense cities and urban areas – all of this facilitates the spread of antibiotic resistance. And I am certain that this is only going to go up with time unless we take relatively drastic measures to curb this.” Rising temperatures due to climate change are challenging human inhabitation in more than one way. With antimicrobial resistance on the rise, human health systems will experience growing precarity as the climate crisis worsens. However, according to a World Bank proposal, an investment of $9 billion in LMICs to combat antimicrobial resistance will alleviate the burden faced by the healthcare systems in affected nations and preserve the efficacy of modern medicine in combating infections. Illustration by Peter Allen.

The UN Climate Change Global Innovation Hub brilliantly — and essentially — envisions reimagining future communities so that fewer resources are needed by design. However, while we are building the blueprint for the future, there are also concrete steps we can take to mitigate environmental damage occurring right now because the climate crisis can’t wait. Some of these measures may even be necessary well into the future. For example, even in a healthier world, the demand for small-molecule drugs and medicines is unlikely to ever vanish, so we should continue optimizing the efficiency of the relevant chemical syntheses. An emerging tool to realize such optimization is metal-organic layers (MOLs). MOLs can be thought of as molecular-scale K’Nex, that is, sets of junctions and linkers arranged to form scaffold-like extended structures. Specifically, they structure themselves as flat sheets of atoms to maximize their available surface area. Scientists then cover this surface area with catalysts, which are small molecules that accelerate and, in some cases, enable the chemical transformations used to synthesize other molecules such as drugs. Once finished, scientists mix the catalyst-covered MOLs into solutions that already contain the building blocks of drug molecules, and the MOL-catalyst structures begin assembling them. By taking the extra step of affixing their catalysts to MOLs, scientists can keep the catalyst molecules from accidentally bumping into each other in solution, a process that typically deactivates both colliding molecules. Thus, the isolated catalysts can continue transforming building blocks into products for much longer, sometimes hundreds of times as long as without MOL supports. The efficiency of myriad processes has been improved with MOLs. Last year, they improved the efficiency of certain cross-coupling reactions by 200 times — even without MOL-based improvements, cross-coupling won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2010. In February, MOLs contributed to the cheapest, most efficient ever synthesis of vesnarinone, a cardiac medicine. MOLs can even directly address the climate crisis — last year, researchers developed a MOL that realizes artificial photosynthesis an order of magnitude more efficiently than previously reported systems. Moreover, this MOL could generate useful fuels such as methane from its supply of carbon dioxide (the potent greenhouse gas) and water. MOLs still suffer from limitations, such as the scale at which they can be produced and the high cost of some of the materials needed to build them. But as successes such as the vesnarinone synthesis make clear, they constitute a worthy topic of future investigation. By Julianne Rolf Climate change is drastically altering the hydrologic cycle. Water vapor concentrations, precipitation patterns, stream flow rates, ice sheet sizes, and cloud formation have been affected. Furthermore, wetlands are disappearing three times faster than forests, driven, in part, by climate change and the resulting sea level rise. Wetlands are some of the most carbon-dense ecosystems, maintaining surface water supplies and acting as a carbon sink. Additional stress is being placed on other potable water resources as both extreme droughts and heavy rains become more frequent. Billions of people do not have access to safe drinking water and sanitation, and 129 countries are not on track to provide these resources for all by 2030. With 3.4 million people dying every year from waterborne illnesses, the United Nations (UN) analysis shows that current progress needs to double to meet Sustainable Development Goal 6. Water production and transportation requires energy, with energy consumption accounting for as much as 40% of treatment costs. Similarly, the energy sector constitutes up to 15% of freshwater withdrawals globally and even more domestically. Water is also essential for electricity generation, mineral mining, oil extraction and processing, and biofuel cultivation. The International Energy Agency estimates that the energy sector will consume almost 60% more water over the next three decades. Certain electricity generation stations will be affected by water cycle changes. Suffering from too much or not enough water can prevent reliable energy access. Extreme droughts can lead to longer fire seasons and larger fires that can disrupt energy supplies. Thus, utility companies, for example in California, have resorted to temporarily cutting their services to prevent fires. Regions with limited or no access to electricity, which are mostly situated in sub-Saharan Africa, suffer from a compounding lack of both clean water and energy. Managing the water-energy nexus effectively and equitably will have significant implications on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for providing clean water, sanitation, and energy to all. We will need to rely on non-traditional water sources, such as wastewater, for drinking water. Less water-intensive electricity generation processes with low or no carbon emissions, such as wind and non-concentrated solar power, will need to be widely deployed. The water-energy nexus should be a priority in future technology and policy changes needed to mitigate the causes and effects of climate change. Without additional incentives from government agencies, power and water treatment plants will not be built or upgraded fast enough to meet the UN Sustainable Goals while simultaneously reducing carbon emissions. By Cailey Carpenter

There’s no doubt about it: large corporations are largely responsible for furthering the climate crisis. How can we, as individuals, help these companies take accountability for their impacts on the environment? The Carbon Majors Report The Carbon Majors Report is an annual collaboration between the Carbon Majors Database and the Climate Accountability Institute to identify the top emitters of greenhouse gasses internationally, namely carbon dioxide and methane. Analysis of the 2015 Carbon Majors data revealed that only 100 companies were responsible for 71% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Although this data is from 7 years ago, many of the top producers from the list remain in the most recent 2018 report. It’s no surprise that these headliners are fossil fuel extraction, refinement, and distribution companies. For years, environmental policy has focused on the replacement of fossil fuel energy sources with renewable energy sources. What about consumer goods? Tackling the large problem of fossil fuel emissions is key, but what about manufacturing of other consumer goods? This is an often overlooked, but important part of maintaining the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement. Industry currently relies on the burning of fossil fuels for energy, and therefore results in 24% of the greenhouse gas emissions in the US. A study by the Rhodium Group found that China, a large industrial center, was responsible for 27% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, followed by the US at 11%. There is a clear correlation between the amount of industry and greenhouse gas emissions, yet this is often overlooked in our climate policies that focus on the largest sector of emissions: transportation. Fossil fuels for energy won’t disappear overnight - once the dependence on non-renewable energy sources is reduced for transportation, the next largest contributor will be industry. Industrial emitters currently have little incentive to reduce their climate impact; the major focus is on being profitable, and fossil fuels are the cheapest and easiest to implement with their ongoing use. This issue likely won’t be a major point of global conversation for a few years, so how can we as individuals begin the push towards climate-cognizant manufacturing? Greenhouse gas emissions policy at COP27 COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland saw the completion of the Paris Agreement Rulebook with the creation of the Glasgow Climate Pact. The Glasgow Climate Pact focuses on maintaining the target of keeping the world temperature from rising more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This agreement has 4 goals: Mitigation, Adaptation, Finance, and Collaboration. Under the category of mitigation, 153 countries agreed on new 2030 emissions targets, and the largest greenhouse gas emitting countries (G20) agreed to return to COP27 with stronger commitments to reducing emissions. At COP27, this commitment was maintained, and discussion focused largely on the implementation of carbon-reducing measures. While this implies stricter policies across all sectors, there was no explicit discourse on reducing the emissions of large industry. It is understandable that the parties at COP27 favored addressing the large topics of energy sources and finance, it is a bit disappointing that big business was not held accountable for their actions. This makes it even more important for individuals to take action. Ways to support green manufacturing practices Reduce your demand. Companies operate on the fundamental principles of economics: supply and demand. By reducing your demand, the supplier has less incentive to manufacture certain products that increase their energy cost (and therefore emissions). Ways to decrease your demand include:

Commit to companies with set plans to reduce emissions. Evaluate the products you use daily, then research these companies and determine how they are handling emissions. Shift your consumption to corporations with a clear plan to reduce energy consumption and handle emissions. Check in every once in a while to ensure they are making progress towards these goals. Not sure where to start? Green Citizen has compiled a great list. Become involved with the government. Contrary to popular opinion, affecting environmental policy does not require you to be a lawmaker. Lawmakers make decisions based on the issues that are important to their communities, so simply voicing your climate concerns can make a difference. Support lawmakers with climate policies that will help us maintain the 1.5°C goal, and who have proven their ability to act on their promises. In democratic countries like the US, support can come in the form of voting, making your opinion known to governments through protests and lobbying, or having a direct impact in creating laws by holding a local government position. by Keith Peterman

Friday November 18, 2022 Greetings once again from Sharm El-Sheikh, Headline today: UN Secretary General and COP27 President urge Parties to restore trust and deliver through much-needed agreements. All here at COP27 recognize the existential threat of climate change. All accept the science and the need for action now – not kicking the can down the road yet another year as has been the case for 30 years since signing the global climate treaty in Rio. However, contentious negotiations continue. No one was happy with the cover draft I sent you yesterday. Parties worked through the night and released a draft text today. Some had softened positions. In particular, the EU supported Loss and Damage and brought others along. Language on fossil fuels is still weak. Those most adversely impacted by climate disruption remain furious that the text does not include “phaseout of fossil fuels”. Too much to write here, but for those of you interested in process, click this link for the latest text – still being negotiated. file:///C:/Users/17178/Downloads/1CMA4_1CMP17_1COP27_preliminary_draft_text.pdf Toward a better world. Thursday, Nov. 11, 2022 For those of you who are following COP27, I will give you my on-site assessment as the COP nears conclusion. First, a statement from the UN Secretary General, “We are at crunch time in the negotiations…The Parties remain divided on a number of significant issues. There is clearly a breakdown in trust between North and South, and between developed and emerging economies.” A draft cover text was released today Few are happy with what is included and what is missing. Loss and Damage In brief, “loss and damage” does not appear in the text. Those suffering the most from climate disasters have contributed the least to its causes. Vulnerable states demand financial help from the countries who became wealthy through consumption of fossil fuels – the root cause of the climate emergency. The wealthy G-20 nations produced 81% of the greenhouse gas emissions in 2021. By contrast, all of Africa produced 4%. Led by the G-77, the global south demands inclusion of loss and damage. G-77 was founded by 77 developing nations in 1964. It currently has 134 members. The global north is expected to pony up the funds. Of note, China and India are both G-20 and G-77 members. I’ve attended multiple press briefing throughout the day by stakeholders including CAN (a network of over 1300 NGOs), the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance, and WWF. These stakeholders demand establishing a Loss and Damage fund at COP28. Quotes:

Quotes:

Of course, the vulnerable nations also demand a “phase out” of all fossil fuels. The wealthy nations want to “phase down unabated coal” and “phase-out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”. From the vulnerable countries’ perspective, this gives a ticket to continue using fossil fuels. It is impossible to stay below a 1.5 deg C increase if we continue to use fossil fuels and generate greenhouse gases. We’ve already used up most of the planetary budget. It's interesting to be here, but frustrating. I’ve participated in every COP since the 2009 COP15 in Copenhagen. We had the grand Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2015. But it primarily laid out goals to be achieved – stay below +2 deg C with ambition for +1.5 deg C. However, action has not yet matched ambition. To conclude, I maintain hope. Everyone here understands the crisis and accepts the need to act. All here recognize that we are out of time. The challenge is to arrive at global cooperation with meaningful action. by Brady Hill ~COP27 Day 2 & 3~ Let's talk methane! First of all, I'm no methane expert. It's been an incredible experience to learn more here at COP27 about the criticality and urgency of methane emissions, tracking technologies, and policies necessary to curb methane emissions in support of limiting overall global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Methane is key to limiting global warming; as such, it's been at the heart of many discussions here at COP27. According to UNEP, methane is 80 times more potent (with regards to global warming ability) than carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere. Methane is responsible for 0.5°C of the 1.2°C of global warming we've experienced so far since the dawn of the industrial era. Per the United Nations, curbing methane emissions is the quickest way that we can limit global warming in our lifetime, and aggressive methane emissions action is projected to enable a 0.3°C reduction in global warming by 2040. Methane is therefore a key focus for humanity in our fight to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Here are some notes regarding methane and COP27 discussions: - Methane reduction is primarily focused on 3 sectors: oil & gas, agriculture, and waste - Given recent advances in methane emission measurement capabilities, we have learned that we are likely underestimating total methane emissions by about 60% in the U.S. - Many solutions to provide more accurate global methane monitoring are not yet operational; as such, the urgency of methane emissions reduction relies on utilizing currently available data to estimate methane emissions to manage and cut emissions in the near-term - Since methane is invisible, measurements from ground, air, and space-based sensors are critical to obtain accurate knowledge of methane emissions sources to inform policies and management efforts - The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. is imposing the usage of empirical data to generate a realistic methane fee program - Standardized, international methane emission reporting is crucial to address emissions globally - Real-time methane emission monitoring, reporting, and transparency is critical such that the public can monitor the progress of countries around the world and keep them accountable Here's a not-so-shameless plug for my company regarding methane and satellite remote-sensing...MethaneSAT (which Ball Aerospace designed and built the sensor for) was just recently named one of Time Magazines top inventions of 2022! https://lnkd.in/gnmsBq8D Here's some other timely links regarding methane and COP27: Biden announces restrictions on methane emissions at COP27: https://lnkd.in/geQD3Q9T United Nations announces that it will launch a public database of global methane leaks detected from space: https://lnkd.in/gfeKEffB https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6998773867083177984?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_feedUpdate%3A%28V2%2Curn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A6998773867083177984%29&lipi=urn%3Ali%3Apage%3Ad_flagship3_search_srp_all%3BO0UE1UF7RhmSHvFX%2FsT7Ww%3D%3D by Brady Hill ~ COP27 Day 1 ~ Today I attended my first day at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, which was the beginning of the second and final week of the conference. Such an incredible, overwhelming, and humbling feeling to be surrounded by world leaders, scientists, industry experts, academics, and other organizations focused on the issues surrounding climate change. Some quick thoughts, highlights, and lessons learned from some of the panels I attended today: - The African Multi-Hazard Advisory Centre was recently inaugurated, which provides early warning systems at the local level for climate-related disasters, trends, and impacts - The non-profit Climate Central just launched their "Climate Shift Index Tool", aimed at enabling the general public to visualize the measurable influence that climate change has on current global climate conditions: csi.climatecentral.org - Novel methods for estimating natural carbon sequestration capabilities of African forests from space are central to Africa leading the global charge in ecological restoration

- Considerations and challenges associated with utilizing water for energy supply are just as critical as those associated with utilizing energy for water supply - Antarctic ice sheet melting can be more attributed to warmer waters flowing underneath the ice sheets than from warmer air in the atmosphere - Since 2010, satellites have been critical to estimate the population of Emperor Penguins and number of colonies through imagery of feces left at the colonies' previous locations (yes, it is visible from space!) - My favorite quote of the day, from a minister at the African Pavilion: "We already possess the technology necessary to address climate change. We are not here at COP27 to develop the wheel – we are here to drive the wheel. Now is the time for action.” By: Emma Kocik

7:00 AM. The bells charm from my alarm and I quickly turn it off. I wish for a few more hours of sleep but my excitement for the day gets me out of bed. I eat a quick breakfast of yogurt and fruit from the local grocery store and proceed to get dressed and ready for the day. My fellow students and I head out for the day, hopping on the shuttle bus that takes us to COP. 9:00 AM. We all arrive at the venue, go through security, scan our badges, and set out on our days. I split from the group to attend a talk at the Cryosphere Pavilion about the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a topic quite relevant to my research topic on the COP coverage of science and policy in the cryosphere. After the talk finishes, I decide to wander around the pavilions, essentially enlarged booths ran by either specific nations or interest groups. I stopped inside the Indigenous People’s Pavilion, where a group of South American indigenous women were speaking about climate justice in their communities. I decided to opt out of the translator and utilize my rudimentary Spanish skills, which was a great decision because the talk became more emotional hearing the passion in their voices. During the talk, it just so happened that I looked to my right and saw U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry walk by, which was an exciting surprise. 12:00PM. The COP tires you out, and after a few hours I was ready for a break. I relaxed for a bit at the U.S. Pavilion, eating my snacks and chatting with those around me. The next event there happened to be a NASA Hyperwall Presentation, so I decided to stick around as I had heard good things. I got to see beautiful satellite images on a large screen and the visuals were interpreted by a scientist presenting. I was lucky to be sitting up front, so I was provided a free NASA book on nighttime satellite imagery. Next, I headed over to one of the main presentation rooms, where I met up with the rest of the ACS crew to watch the Gap Report, which essentially summarizes the successes and failures of the parties in achieving their 2030 climate goals. While it was tough hearing the shortcomings of the year, it was motivating to see U.S. emissions dropping in particular. 3:30PM. Part of the group and I decided to head over to the Green Zone for the afternoon. The Green Zone is the area of the COP open to the public and is filled with art to browse and many booths from industry, academia, and other sectors. We spent some time engaging with the booths as well as buying local artwork from some artisans. After, we walked through the Biosphere exhibit, which contained dark rooms filled with protections representing different biological systems on Earth. Finally, we grabbed a bite and headed out on the buses after a long day. 7:00PM. We arrive at our AirBnB. For the next couple of hours, we hung out and worked on updating various channels of social media. I am taking over the Instagram of my undergraduate college, Chapman University’s Schmid College of Science & Technology, this week, so I edited some photos of the day to publish. Finally, I planned out my schedule for the following day, and exhaustedly climbed in bed. 12:30PM. by Anna Lisa

My goal for COP27 is specifically to study the effects on Indigenous communities of mining different battery materials, the findings of which I will present at the American Chemical Society conference in the Spring. That being said, there’s no reason not to explore some unique events while I’m attending this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. On November 14, I visited the Korean Pavilion to attend a talk on the unique role of K-Pop (Korean popular music) in climate action. Watching this panel of young women present on the problems and potential associated with the cultural phenomenon, I saw the future of climate conversations. While K-Pop is distinct, it presents the same modern elements that are emerging in several industries. For one, there is a sharp conflict between the labels’ promotion of mass consumerism and youth’s demands for climate action. The companies promoting K-Pop artists encourage mass consumerism by releasing special edition albums, ranking artists by album sales, encouraging physical album sales through raffles, etc. The music streaming time spent by K-Pop fans is about twice as long as that spent by the average user. At the same time, this generation regards climate change as a top priority, and, as one panelist pointed out, they don’t want to feel guilty listening to the music they love. Generation Z and Millennials hold high standards of moral accountability to the companies they patronize. Whether it’s the record label that signs their idols, the streaming platform through which they play their music, or some other business in the music industry, many young consumers demand that the money they spend doesn’t contradict the issues they care about. As one panelist said, the K-Pop fandoms are “not a follower, but an active partner” with the companies that they patronize. Finally, greenwashing. For example, although the K-Pop group Dreamcatcher and others sing to the existential fears of their young fanbase, they do not follow this up with strong action in their merchandising. Most K-Pop albums are often physical and packaged in non-recyclable plastic. By giving customers the facade of action, companies are able to dodge accountability. Interestingly, often within the K-Pop industry, the intentions of the singers and those of their record labels are entirely different. Many K-pop idols express genuine concern for climate catastrophe, typically spurring action from their respective fandoms, while their signing labels keep the interest of profits first and foremost. While K-Pop is distinct, it presents the same modern elements that are emerging in several industries, like the conflict of mass consumerism and climate concerns, high ethical accountability of labels to consumers, and greenwashing. In discussing climate solutions in the K-Pop industry, the panelists were envisioning the future. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed